By Anjan Roy

Had he been alive, Rajiv Gandhi would have been somewhat of an old man today. He would have crossed 78. But he remains for ever a young man who had once said that he had a right to dream — dream about India.

Rajiv Gandhi was a reluctant politician. He was brought into politics by his mother, Indira Gandhi, and when she was asked about the performance of her latest “General Secretary” at the AICC session in Calcutta, she had become furious.

The question posed by one of the journalists at an evening informal press interaction was taken as a personal affront by the fiesta prime minister that Indira Gandhi was. Rajiv Gandhi had just been inducted into Congress Party as a general secretary and to be honest his performance was nothing to write home about.

At the session earlier that day, Rajiv Gandhi had been making his first speech at a big gathering. From the dais he made a spectacle about it, messing up data and information. H was being promoted by Pranab Mukherjee, who was sitting by his side to help him give a cogent speech.

However, that was not to be. Pranab Mukherjee was prolific with data and details. Rajiv Gandhi was, if anything, just the opposite. He had very little grasp of data and facts, and in those early days, he really did not have much of an idea of how the economy was doing in details.

But Rajiv Gandhi’s winning point was his charm. He was at the end of the day a good man and it came out in every interaction. He was well-meaning and had a vision of India’s future which was modern.

Today’s India would have been different but for Rajiv Gandhi’s short tenure as prime minister from 1984 to 1989. He had bought in Sam Pitroda as head of several technology missions. Of these, the most important was the Telecoms mission.

Sam Pitroda was a telecom expert and he set up what was then known as “C-DoT” which had developed some special telecom exchanges for rural areas and penetration of telecom network. There were several other steps which brought about a qualitative change in India’s telecom backbone.

It was in those years that gradual opening up of the telecoms network to the private sector began. This single step, liberalising and paring away the stranglehold of the government over telecoms service provision, had laid down the foundation of later IT revolution in the country.

After all, without reliable and extensive telecoms network, India’s IT and IT enabled services could not have become the global force that it has subsequently become. One only remembers the struggle and expenses of making inter-city calls in the 1980s. It used to be nightmares.

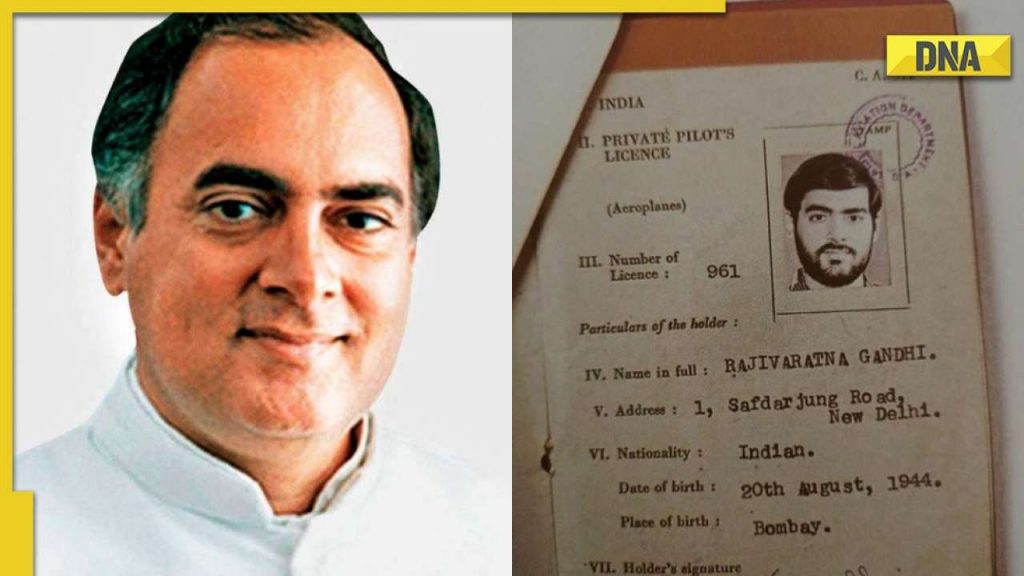

The most critical other forward movement was in opening up the civil aviation sector to competition. Himself a qualified pilot he had flown the aircraft belonging to public sector Indian Airlines. He had seen the way the trade unions of different segments of the two public sector airlines staff would hold the entire industry to ransom.

If the ground engineers would strike work one day, the pilots guild would suspend flying on demands of some allowance or facilities the other day. It was simply put exasperating. Getting a confirmed air ticket from Calcutta to Delhi or any other pairs of cities would mean calling up Airlines House and request for a favour.

Beginning with air taxi services, Rajiv Gandhi’s initial tentative steps had liberalised the entire airlines sector. Today I wonder how many people fly in India and how could that have been possible without those initial thoughts about opening up the Indian airlines industry from exclusive dominance of the public sector.

Rajiv Gandhi had realised the importance of having computers and made imports of these gadgets cheaper. The hardware was as much important and essential as anything else that egged on the country towards a new beginning. These were all part of the Rajiv Gandhi dream of mid 1980s.

The reforms and opening up, including imports, had admittedly contributed towards an evolving crisis at the beginning of the next decade. India had faced an external payments crisis in the beginning of the 1990s.

With hindsight that crises looked more like a blessing in disguise of a curse. Without that deep crisis, India would never have thrown off the yoke of a huge load of rules and restrictions which had encrusted the Indian economy into a mould. The economy would not have come out of that mould, and it stagnated to crawl.

It was the most unlikely character of a Narasimha Rao who, through the instrumentality of Dr Manmohan Singh, removed cobwebs of strangulating restrictions. But the beginning was surely made by Rajiv Gandhi.

He was a decent man, above all. I had the good fortune of participating in an outreach experiment that Rajiv Gandhi had initiated in the years he was out of power. He used to meet journalists in the library room of Ten Janpath. In an atmosphere of informality and free-wheeling discussions Rajiv Gandhi could broach many of the issues which were not just in current coin.

These issues he would like to discuss were off-beat and had much wide-spread implications. I remember he was thinking of the impact that the television revolution would have on society and politics. How could you restrict Indians from viewing news and current affairs programmes or even soap operas beamed from other countries.

The solution, he felt, in restricting Indian from viewing these but allowing a crop of Indian TV companies which would provide a varied fare in competition with the global ones. The policy implication was to liberate Indian TV from the exclusive clutches of Doordarshan and open it up to competing channels

But today’s remembrance of Rajiv’s memory could not possibly ignore what the current Congress spokesman, Jairam Ramesh, had dug up from records.

Ramesh had re-Tweeted Atal Behari Vajpayee recalling how India’s prime minister had gone out of his way to enable the Opposition politician that Atal Behari was then to enable him to get medical treatment in the USA which the latter was otherwise unable to organise.

Vajpayee had developed some kidney ailment. Rajiv had come to know of it. An Indian delegation was going to the UN headquarters in New York. The prime minister Rajiv Gandhi had informally called the Opposition politician Atla Behari to his chamber and nominated him as a full official member of the Indian delegation to the UN session.

After the session, Vajpayee could stay back and get full medical attention. That made possible for Vajpayee to get the medical treatment he needed. Maybe, that prolonged his life long enough to become the BJP prime minister of India.

It was these civilities that had defined Indian politics under Rajiv Gandhi which is rare to see today. (IPA Service)

A Coastal Community’s Struggle For Protection Of Their Livelihood, Habitat

A Coastal Community’s Struggle For Protection Of Their Livelihood, Habitat