By Shreenivas Khandewale

In a democracy, it is said, whatever the policies and implementation, the opposition and others will criticise the Government. But the government, on its part, thinks and says that since opposition is criticizing, its policies must be correct.

The present day economic scenario represents such a situation. For example, the Asian Development Bank (ADB) had projected in April 2022 report 7.5 per cent and 8.0 percent as GDP growth rates for India during 2022-23 and 2023-24 respectively. In July, it revised downwards those rates to 7.2 per cent and 7.8 per cent respectively and now, in September 2022, it has further revised downwards the GDP growth rate for 2022-23 at 7.0 percent.

Similarly many rating companies and economists have voiced their concern for the slow, uncertain, declining rate of growth and for the recovery process.

Similar is the case of Current Account Deficit (CAD) and inflation. The CAD implies expenditure higher than revenue, to be financed by incurring the public debt. It is calculated that the deficit in 22-23 may be record high for the last 8-9 years (i.e. the tenure of the present government)! The public debt reached an unsustainable level of Rs. 135,87893 crore on 31st March 2022 and is expected to reach the level of Rs. 152,17,910 crore by March 31st, 2023.By March 2022 the public debt formed 55per cent of the GDP, up from 42 per cent in 2019.India’s total debt in June 2014 was mere Rs.54,90,763 crore. The crease by 2023 represents a staggering 177 per cent jump.

The inflation in India is high and sticky around 7 per cent, that is above the tolerance limit of 6 percent fixed by the government for itself. The basic question is whether common man’s wages are rising at that rate to enable him to cope with inflation? If not, then the standard of living of the masses is falling.

Next, the surplus of the GDP growth rate over and above the rate of inflation is supposed to be available to the government for development purposes. In the instant case, it is argued by some experts, if inflation rate could be brought down to 4 percent, then ideally 3 percent surplus GDP would-be available to the government for development and welfare purpose.

But with 7 per cent GDP growth rate and 7per cent inflation, with no surplus remaining, a disappointing picture emerges, about which the general masses need to be made aware. Since the government has a policy of not enhancing the direct (Income, Corporate etc.) taxes, the burden of repayment of public debt, payment of inflated prices etc. falls mainly on the low and middle income groups. The Finance Minister, however, assures the countrymen by saying that growth is robust and inflation is under control!

The Finance Minister has an economic puzzle. At the Mindmine Summit held in the third week of September, she expressed her bewilderment by observing about the corporate sector that for the delayed payments to the tune of Rs.10 lakh crore to the MSME sector, apart from the Government Departments, big corporate companies were also responsible.

The Government substantially reduced the company taxes to help the corporate sector, a favourable Production Linked Incentives (PLI) scheme has been implemented for the corporate sector, but the corporate sector was not investing capital for long term development. Therefore, employment is not being created, GDP growth is not being ensured.

The Minister was really at pains and publicly observed, “I want to hear from India Inc; what is stopping you.” A report by Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE) has observed: “For three consecutive years since 2019-20, growth has been fuelled by growth in better asset utilization and the contribution of growth in assets has been negative.”

The situation becomes more fearful, looking at the haste in which mindless privatization of public sector is being pursued by the Government. The danger is that once public sector is totally privatized, the nation will be totally at the mercy of the corporate sector for production of goods and services; level of employment, level of wages and income distribution etc. And the Government will be found pleading with the corporate sector as it is doing at present. What would happen to the employment of youth in the second most populous country is anybody’s guess.

With the policy of economic liberalisation adopted in 1992, the public sector was dominated by the private (corporate) sector. The abuse of peoples’ money in the public sector banks, by a huge majority of corporate enterprises and silence over the abuse by the managing boards (especially the independent directors) is the frightful scenario of the future privatized banks of India. Some of the facets of the emerging situation may be visualized thus:

(1) The changed pattern and volume of production may alter the material culture of the society.

(2) The continued emphasis on labour-saving technology may not create adequate jobs, making unemployment a permanent feature of the economy.

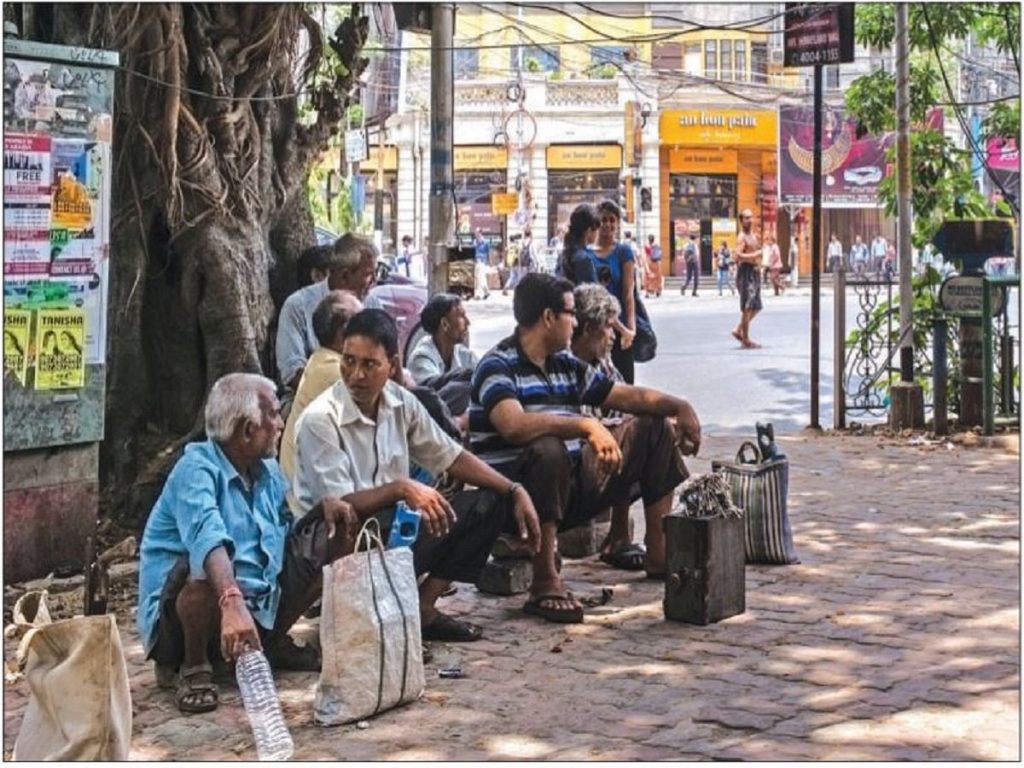

(3) Large-scale unemployment of youth with no or little incomes on the one hand and tax concessions to upper income classes have already created and widened not only the income inequalities but also class inequalities in India. The exacerbated inequalities have a tendency to generate crime and violence in many old and new forms, as can be seen even at present.

The above-mentioned dimensions of the changed economic structure are engulfing the other sectors like agriculture, health, education, art, literature etc. To think and to say that other countries are facing similar problems does not help us in solving India’s problems. Problems generated in Indian economic reality require thinking rooted in the Indian political economy. But it has two pre-conditions, like (1) The thinking must aim at a systemic change, and (2) It must be within the framework of the Indian Constitution. (IPA Service)

Nitin Gadkari Is Right – India Is A Rich Country With Largest Poor Population

Nitin Gadkari Is Right – India Is A Rich Country With Largest Poor Population