India’s water issues are frightening and complex. The ‘sarkaar’ and the ‘bazaar’ deal with these in their own framework. Photo: Priyanka Parashar/Mint

India’s water challenges are intractable, messy and perennial. While citizens wait for the state to deliver on its obligations, they also scramble for their own solutions, some old, some new, some workable, some not so much.

With the summer looming, water comes more easily to the urban mind. Even for those who had been reasonably secure all year long, it is an uncertain time. Maybe it is time to build a sump, to invest in a rainwater harvesting system, or to try, again, to dig a private borewell.

Apartment residents may finally succumb to the new water saving aerators that they have resisted; that neighbours keep boasting about. They feel more ready to pay up for the new recycling plant the association wants to install.

Borewell entrepreneurs are preparing too. There will be much demand for their services. They are innovating furiously to coax out water from the unyielding aquifer. Their livelihoods depend on it.

Open wells are making a comeback. People hunt for the remaining old-timers who knew exactly how to excavate the precious, hidden groundwater.

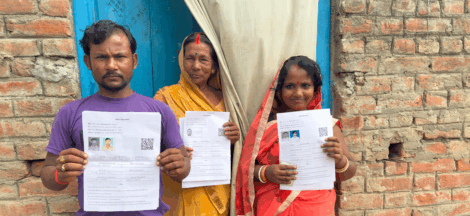

In slums everywhere, the daily battles are made easier thanks to water ATMs, put up by politicians, philanthropists or aid agencies. For Rs5, or Rs10, clean drinking water for the family will be available, even in the harshest months.

By now, farmers everywhere, especially in rain-fed areas, feel the familiar anxiety building up. Their old knowledge systems, honed over centuries, are failing them. The meteorological department is getting more accurate in its predictions but the monsoon itself is changing. It rains too much at once, rains when it should not, drizzles when it should pour, or rains where it never has. How does one plan in such a situation? When to sow, what to sow, where to sow?

Some of them have been experimenting with drought-proof crops. Millets are capturing the imagination again. There is a strong urban demand for ragi, jowar, bajra, and more. Where market linkages are built, farmers are growing more of the crop their grandfathers did, with less water.

Farmers in areas downstream of large cities sometimes reap an unexpected bonanza, even without rain. Bengaluru lifts up water at great cost from the Cauvery, perhaps depriving farmers along the way. But after use, it releases volumes of wastewater that flows to the Hoskote valley. Cities are now irrigation streams, creating new possibilities of symbiotic water management.

Other farmers are worried about too much water, especially in the Gangetic plains. They are tired of living in a flood economy, with their assets literally being washed away every year. Some wish they could just bottle all the water and sell it like the big companies do. But they too are experimenting with crops that can withstand flooding.

In the western desert, communities are planning to capture every drop of rain. They are past masters at it, and will do it again. Some are switching to solar energy as a better income source than agriculture. Now, though, they are telling each other a new cautionary tale. It might rain too much this year, as it did a while ago. They must prepare for unfamiliar diseases like dengue and chikungunya.

In the North-East, people are fed up waiting for piped water. They are combining traditional wisdom with modern practice to revive the thousands of springs that flow through their lands. These springs then feed the rivers, and grateful populations downstream benefit from the hill people’s efforts.

In the southern forests, it is already scorching hot, and the water bodies are drying. Environmentalists work with the forest department to dig and fill up tanks with groundwater drawn by solar-powered pumps. Now, the tiger and the deer will have water to drink and the tourists can quench their thirst for good photographs.

At the peninsular coastline, too many rivers do not flow to the sea anymore. Farmers worry as the ocean begins to creep into the land, rendering farms saline. They valiantly try pisciculture, or plant new crops that tolerate brine.

Scarily, new quality issues emerge everywhere. Salt, fluoride, arsenic, nitrates and heavy metals show up in drinking water.

Old remedies like eating amla are combined with several new filters and technologies, some of which give only psychological relief.

India’s water issues are frightening and complex. The sarkaar and the bazaar deal with these in their own framework. But this is a glimpse of the samaaj’s imagination, and the people’s response to emerging water challenges.

Rohini Nilekani is the chairperson of Arghyam.