NEW DELHI: For a country that harbours hopes of fast emerging as a developed nation with a seat at the high table as the third-largest economy on the planet, growth numbers matter. Veteran banker and economist Dr C Rangarajan has often said that India needs to grow consistently at 8 to 9 per cent per annum for at least two decades to get to the per capital income levels of the rich nations.

Therefore, when the country posted a low GDP growth rate of 5.4 per cent for the second quarter of FY25, there were concerns. Finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman tried to allay fears of a slowdown and was quick to describe it as a “temporary blip” even as the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) downgraded its GDP forecast for the fiscal year 2024-25 to 6.6 per cent from 7.2 per cent earlier.

In the closing days of December and an inescapable sense of standing in the doorway, with one foot in the past and the other in the future, it is time to reach out to Dr C Rangarajan on what the former chairman of the Prime Minister’s Economic Advisory Council and the former RBI governor expects and what may be likely.

To him, it is still reasonable to expect the current fiscal year to conclude with a growth rate of between 6 and 6.5 per cent (with 6.5 as the outer limit, he cautions). His bigger concern is not the immediate numbers but what we seek to do over time and on ensuring sustainable high growth conditions.

First, his reading of the current numbers: “The first two quarters of the current financial year taken together give us about 6 per cent growth for the first half of the fiscal year. This again is driven by the rather reasonable growth posted in the first quarter as against the slippage to a less inspiring 5.4 per cent in the second quarter. To this, if we stick to the projections made earlier by the RBI for the third and fourth quarters, we may end up with a 6.5 per cent growth for the year as a whole. But then, this to me seems an optimistic number because the original growth projections for the third and fourth quarters were in line with a higher second quarter growth that were originally indicated. So, perhaps a 6 per cent growth for a year as a whole may still be possible.”

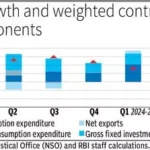

So, what can one expect in the coming year in the light of the dip in the second quarter growth number. “My major contention is that the steep fall in the second quarter growth rate is primarily because of the decline in the government expenditure and in particular, the government capital expenditure. In fact, the growth rate in the capital expenditure by the government was negative in the first half of the year. It contracted by (-)15.4 per cent during the first half of 2024-25.” But then, he reminds, “considering that it is a variable that is under the control of the government and therefore we could see a reversal in the second half of the year with the government raising the capital expenditure.” Therefore, if the government does end up raising the capital expenditure in the third and the fourth quarter, which they may well do since it is in their control, then a 6 per cent GDP growth is quite possible, he says.

According to Dr Rangarajan, if the government is to realise its annual budgeted growth rate then its capital expenditure will have to grow by around 60 per cent in the remaining part of the fiscal year.

As far as production is concerned, he sees manufacturing as an area of concern because slow growth rate in manufacturing also has implications for growth rate in employment, which has been in the spotlight by various economists. His observations matter given the stickiness in the manufacturing sector growth rate at around 16 per cent of GDP.

Dr Rangarajan is not particularly concerned about the immediate numbers but seems more curious about the enablers that need to be put in place to ensure sustainable high growth years. He says: “The growth rate in the last few years has been particularly stimulated by government capital expenditures. So, for the immediate future, one need not be deeply concerned (as the government may opt to step up the capital expenditure) but over a period of time, we have to look at the fact that the economy cannot be run by the stimulation caused by the government capital expenditure alone. Also, this has to be sustained by a high fiscal deficit, which again is not sustainable and if the goal remains to lower the fiscal deficit then the freedom to raise the capital expenditure gets curtailed. The focus therefore has to be on private sector capital expenditure going up.”

His solution: “The government needs to find out the areas in which the private capital expenditure has not been increasing and take necessary actions in order to stimulate the private capital expenditures in those areas. One way to trigger this is by raising the government capital expenditures in the remaining two quarters and get to around 6 per cent growth for the fiscal year as a whole and this may make the private sector come forward with higher investments.

For instance, higher capital expenditure on laying railway lines will see a pick up in the case of the steel industry.”

He therefore says, “we really need to see how far the government capital expenditure is closely aligned to the capital expenditure of the private sector so that it stimulates the private sector expenditure.”

As far as inflation, another area of concern, Dr Rangarajan sees the country typically dealing with food inflation between September and December. So, it is quite possible that it may now fall. Therefore, for the year as a whole, we may still stay within the range, he feels.

Overall, looking back at 2024, the calendar year, Dr Rangarajan finds it a good year with the first two quarters since January, 2024, posting high growth rates and during the calendar year with only one bad quarter, the growth was almost at around 7 per cent. What now remains to be seen is how the calendar Year, 2025 unfolds and the narrative that will follow for the India growth story.

Source: The Financial Express

Indian Economy And The Financial System Remain Strong And Stable: Financial Stability Report

Indian Economy And The Financial System Remain Strong And Stable: Financial Stability Report