By Jeff Schuhrke

On a visit to Chicago in 1988, Uruguayan journalist and historian Eduardo Galeano asked local friends to take him to Haymarket Square, the place forever associated with, as he put it, “the workers whom the whole world salutes every May 1st.” He was quickly disappointed by what he found. “No statue has been erected in memory of the martyrs of Chicago in the city of Chicago,” Galeano lamented a few years later. “Not a statue, not a monolith, not a bronze plaque. Nothing.”

In Uruguay, as around the globe, the Chicago anarchists executed in the 1880s while fighting for the eight-hour day have long been considered labour martyrs. But as Galeano’s fruitless search for a memorial demonstrates, in the United States — particularly in Chicago — the memory of the Haymarket martyrs has traditionally been suppressed, and the meaning of what happened to them has been contested for well over a century.

Reactionaries and those in power have typically presented the Haymarket affair as the quintessential story of “the thin blue line,” in which heroic police officers saved civilization from a lawless mob of terrorists. As recently as October 2020, in the wake of the George Floyd uprising, Chicago mayor Lori Lightfoot compared the current moment to the 1880s, when “people feared for their safety from groups of anarchists who routinely created chaos in the streets.”

But generations of Chicagoans — including many that voted out Lightfoot this year and elected progressive trade unionist Brandon Johnson — have rebuffed that narrative. They instead tell a story of exploited workers struggling for human dignity, having their lives deliberately destroyed, and yet meeting their fate with courage and thus inspiring a movement for working-class liberation.

While the epic of the Haymarket affair has rightly been told and retold countless times, the story of this battle over historical memory — and how it specifically played out in Chicago — remains relatively unknown.

On May 1, 1886, hundreds of thousands of US workers went on strike and marched to demand the eight-hour workday — a day of action called by the Federation of Organized Trades and Labour Unions, the precursor to the American Federation of Labour. Thanks to radical labour organizers like Albert Parsons and August Spies, Chicago saw the biggest demonstrations of the day, which remained peaceful.

But two days later, police shot several striking workers at the city’s large McCormick Reaper Works as they scuffled with scabs. Witnessing this firsthand, a horrified Spies called for a rally to “denounce the latest atrocious act of the police.”

The next night, May 4, around 2,500 workers — most of them immigrants — gathered at Haymarket Square to listen to local anarchists deliver speeches from atop a wagon. Mayor Carter Harrison was in attendance and judged the gathering to be “tame.” As the rally wound down and the crowd dwindled to two hundred people, Harrison headed home, but not before telling the 175 police officers stationed a couple blocks away to stand down.

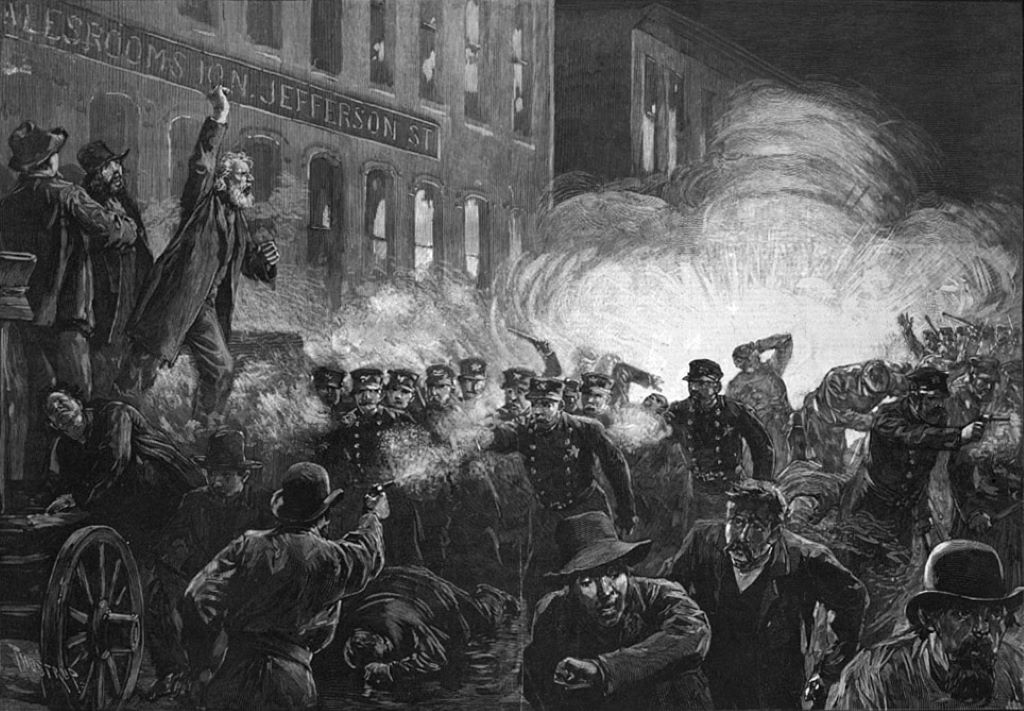

Ignoring the mayor’s instructions, the police marched toward the protesters and ordered them to disperse as the last speaker was wrapping up. That’s when a still-unknown assailant threw a homemade bomb into the phalanx of cops, which immediately exploded. Frantic, officers began shooting wildly, and some of the rally-goers allegedly shot back. In the end, seven police officers and at least three workers died. Officer Mathias Degan was killed by the eruption, but historians generally believe the other cops died after being hit by friendly fire from fellow officers.

The business press immediately labelled the incident “the Haymarket Riot” and demanded blood. Martial law was declared in the city. Chicago police ransacked union halls, radical newspapers, and private homes, arresting hundreds of anarchists, socialists, and labour activists without due process.

That summer, eight of the city’s most outspoken anarchists — Parsons, Spies, Adolph Fischer, George Engel, Louis Lingg, Samuel Fielden, Michael Schwab, and Oscar Neebe — were put on trial for the murder of the seven police officers. With no physical evidence directly tying the men to the bomb, they were instead tried for their revolutionary beliefs and found guilty.

The judge sentenced Neebe to fifteen years in prison, but the other seven were condemned to execution. Over the next year, Lucy Parsons, Albert’s wife and fellow anarchist, led an international campaign demanding clemency for the men, whom sympathizers began calling the Haymarket martyrs. Radicals, liberals, and trade unionists worldwide rushed to support the cause, viewing the trial as a sham and an attempt to crush the labor movement.

The Illinois governor commuted the sentences of two of the condemned men — Fielden and Schwab — to life in prison, but did nothing to spare the lives of the others. On the eve of the scheduled executions, Lingg died of an apparent suicide in his jail cell. Parsons, Spies, Fischer, and Engel were hanged together on November 11, 1887. They were buried in Waldheim Cemetery in the western suburb of Forest Park — no graveyard in the city was willing to accept their remains.

On May 1, 1890, invoking the memory of the Haymarket martyrs, workers in multiple countries staged strikes and demonstrations demanding the eight-hour day. From then on, May 1, or May Day, was International Workers’ Day.

But in Chicago, a struggle over the meaning and memory of the Haymarket affair exploded almost immediately — and has continued for over a century.

In September 1887, six weeks before the execution of the convicted anarchists, a group of prominent Chicago-area businessmen launched a fundraising drive to build a monument honouring the police officers killed and wounded at the Haymarket affair. With the Chicago Tribune hyping the campaign, the group quickly raised $10,000 to erect a nine-foot-tall bronze statue of a cop with his arm outstretched and palm facing forward. An inscription on the pedestal read: “In the name of the People of Illinois, I command peace.”

The police monument, which was placed in Haymarket Square, sparked protest even before its official unveiling in May 1889. On May 3, 1889, a leaflet was placed on the new monument’s pedestal asking, “Have you ever given a thought to . . .the base murder of five of the real victims of the haymarket tragedy…?” The anonymously authored pamphlet continued: “The time will come for an ample justification of our comrades, but it is not quite yet. On the monument at the haymarket should be inscribed in letters of fire these words: ‘Erected to commemorate the strangling of free speech and the shame of an enslaved people!’”

Authorities shrugged off this “blatant anarchist screed,” as the Tribune called it, and moved forward with the police monument’s dedication ceremony on May 30, Memorial Day. Meanwhile, the widowed Lucy Parsons and her comrades established the Pioneer Aid and Support Association to solicit donations for the families of the Haymarket martyrs. The association also raised money for a monument at the site of the martyrs’ tomb — a response to the police statue in Haymarket Square.

After nearly six years, enough money had been collected for sculptor Albert Weinert to build the Haymarket Martyrs’ Monument: a statue of a hooded woman, representing Justice, protecting a fallen worker and placing a laurel wreath on his head. August Spies’s final words from the gallows are inscribed on the monument: “The day will come when our silence will be more powerful than the voices you are throttling today.”

On June 25, 1893, at a ceremony attended by eight thousand people, the monument was unveiled at the grave of the executed anarchists in Waldheim Cemetery. The following day, Illinois governor John Peter Altgeld — a prolabor Democrat elected the previous November — pardoned the Haymarket anarchists, freeing Fielden, Schwab, and Neebe while excoriating the trial and executions as a gross miscarriage of justice.

Altgeld’s pardon, along with his refusal to support the deployment of federal troops to crush the Pullman strike the following year, effectively ended his political career. He lost his reelection bid and never held public office again.

In the decades following the Haymarket affair, as trade unionists and radicals around the world cemented the tradition of marking May 1 as International Workers’ Day, the Haymarket Martyrs’ Monument became a place of pilgrimage for leftists and labor activists.

Eugene Debs, who had led the 1894 Pullman strike and would later become the standard-bearer of the Socialist Party, paid a visit to Waldheim Cemetery in the late 1890s and penned an essay celebrating the Haymarket anarchists. Describing them as “the first martyrs in the cause of industrial freedom,” Debs wrote that he looked forward to the day “when the parks of Chicago shall be adorned with their statues.”

Around the same time, famed anarchist Emma Goldman also came to Chicago and paid her respects at the monument, which she called “the embodiment of the ideals for which the men had died.” At her request, Goldman was herself buried at Waldheim in a grave plot near the Haymarket anarchists after her death in 1940.

As for the police monument at Haymarket Square, after nearby property owners complained that it took up too much space, it was moved about a mile west to the intersection of Randolph Street and Ogden Avenue in 1900. Every year on May 4, the Veterans of the Haymarket Riot — an organization of surviving police officers from the night of the bomb — would gather for a memorial service in front of the statue and rededicate themselves to preserving “law and order.”

On May 4, 1927, a streetcar making the turn from Randolph to Ogden jumped the tracks and crashed into the monument’s pedestal, toppling the statue. The motorman claimed it was an accident caused by unresponsive air brakes, but legend has it he was later overheard saying he “was sick of seeing that policeman with his arm raised.” It is indeed a curious coincidence that the collision happened on the anniversary of the Haymarket incident. To avoid similar traffic accidents, the police statue was moved the following year to nearby Union Park, where it would remain mostly out of sight for the next three decades.

During the great labor upsurge of the 1930s, a new generation of working-class radicals — particularly the youthful Communist organizers of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) — embraced the legacy of the Haymarket martyrs. In early 1938, the CIO-affiliated, Communist-led Farm Equipment Workers Union (FE) successfully unionized International Harvester’s Tractor Works — the McCormick family–owned plant where August Spies witnessed police brutalizing strikers in 1886, prompting the fateful Haymarket rally.

For years, Chicago officials rejected the ILHS’s appeal for a new monument or park in Haymarket Square. “It’s all a part of a deliberate amnesia,” Orear complained. “Our story is that Haymarket was a police riot — nobody did a damn thing till the police came. Their story is that [the incident] saved the city from anarchist terrorism.”

In May 1986, a coalition of artists, activists, unionists, teachers, historians, clergy, and other community members came together to commemorate the centennial of the Haymarket affair. Scores of public events were held around Chicago, including marches, rallies, art exhibits, poetry recitals, a dramatization of the Haymarket trial performed by members of Actors’ Equity, and musical performances by Pete Seeger, among others. Mayor Harold Washington gave his stamp of approval to the festivities by declaring May 1986 “Labour History Month.”

Finally, by the early 2000s, the city agreed to erect a new monument in Haymarket Square.

Made by artist Mary Brōgger, the Haymarket Memorial was dedicated in September 2004 — over 118 years after the bomb was thrown. Located at the exact spot where the speakers’ wagon stood on the night of May 4, 1886, the memorial is a rust-coloured sculpture depicting a wagon with human shapes speaking atop it.

At the dedication ceremony, the presidents of both the Chicago Federation of Labour and Fraternal Order of Police gave speeches — and each was heckled by different crowd members with competing interpretations of the Haymarket affair. “Over the years,” a carefully worded plaque on the memorial’s base reads, “the site of the Haymarket bombing has become a powerful symbol for a diverse cross-section of people, ideals and movements.”

Despite the memorial’s intended ambiguity, it has been claimed by the labour movement and frequently serves as a rallying point for marches organized by leftist protesters of various stripes.

Not to be outdone, in June 2007, the Haymarket police statue was again refurbished, given a new pedestal, and moved to Chicago Police Headquarters on South Michigan Avenue. The rededication ceremony featured the great-granddaughter of Mathias Degan, the one officer historians agree was killed by the bomb.

In recent decades, Chicago’s growing working-class Latino community has embraced the Haymarket story, which is perhaps not surprising given the almost saintlike status of the Haymarket martyrs in Latin America’s labour movements.

On May Day 2006, up to four hundred thousand Latino workers marched in Chicago as part of the historic “Day Without Immigrants” demonstrations, some of them stopping to pay homage at the new memorial in Haymarket Square. A few weeks later, Eduardo Galeano returned to the Windy City during a book tour and discussed the significance of the Haymarket affair with some of the local unionists who had led the march.

Latino Chicagoans especially celebrate Lucy Parsons, who claimed Mexican ancestry. In 2017, a portion of Kedzie Avenue in the Logan Square neighbourhood, near where Parsons resided for several years, was honorarily named “Lucy Gonzales Parsons Way” with support from socialist alderman Carlos Ramirez-Rosa. Fellow socialist Anthony Quezada, a newly elected Cook County commissioner, successfully introduced a resolution last month formally recognizing May 1 as International Workers’ Day and commemorating the lives of the Haymarket martyrs. And last year, young Latino artists with Yollocalli Arts Reach — the youth initiative of Chicago’s National Museum of Mexican Art — painted a new mural of the Haymarket martyrs on the exterior of Grace Elementary School in the city’s Little Village neighbourhood. The mural is titled “Que La Libertad Nos BeseEn Los LabiosSiempre” (“May Freedom Kiss Us on the Lips Forever”).

“You have to swim in whatever pool there is and rebuild and rebuild,” said the ILHS’s Orear, who died in 2014 at the age of 103. “This is the story of American labor — defeat, starvation and rebirth.” (IPA Service)

Courtesy: Jacobin

Workers Rallies Throughout The World Observed May 1 With Vigour

Workers Rallies Throughout The World Observed May 1 With Vigour