By Bill V. Mullen

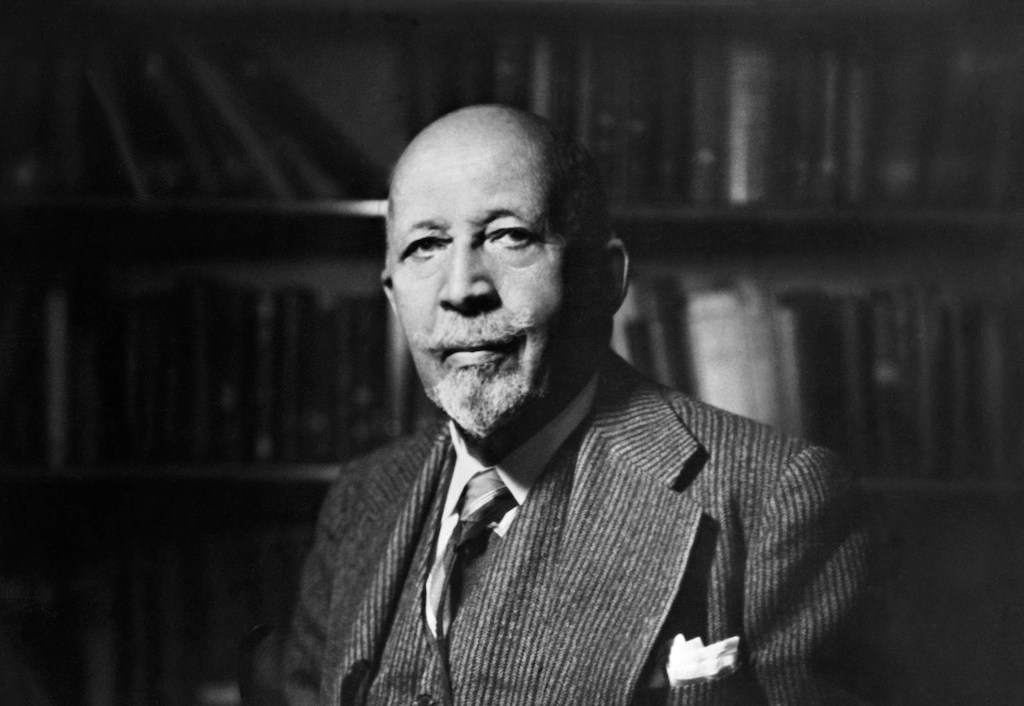

W.E. B. Du Bois is still the most famous black American Communist in US history, and the godfather of what has been called the black radical tradition. Best remembered for his remarkable work Black Reconstruction in America, he remains a vital reference point for those organizing against the violent forward march of capitalism.

Du Bois viewed every political question as a radical internationalist, querying how capitalism, imperialism, and colonialism had become the triple-headed monster of modernity. One solution he arrived at to all three problems was Pan-African socialism.

Du Bois’s career as a Pan-African socialist began with his chapter on the Haitian Revolution in his 1895 Harvard dissertation on the African slave trade. He later lamented that the dissertation suffered from a lack of education in Marxism — as a student, he wrote, “I was overwhelmed with rebuttals of Marxism before I understood the original doctrine.” Yet the attention he paid to Caribbean slavery and workers’ uprisings marked his first effort to see the African diaspora and capitalist history as a totality.

In Berlin on a Slater Fund Fellowship while at Harvard, Du Bois attempted to fill in his socialist education, attending meetings of the new Social Democratic Party (SDP) in the working-class district of Pankow. After the meetings, he wrote, “I began to see the race problem in America, the problems of the peoples of Africa and Asia, and the political development of Europe as one.”

In 1897, Du Bois presented a paper, “The Conservation of Races,” to the American Negro Academy in the United States. Heavily influenced by nineteenth-century writer, minister, and Africanist Alexander Crummell, Du Bois argued for the history of the world as a history of “races.” Negroes both African and American, he argued, were common “members of a vast historic race that from the very dawn of creation has slept, but half awakening in the dark forests of the African fatherland.”

The essay represented Du Bois’s first step toward a Pan-African philosophy. It helped draw him to London, where in July 1900 he attended the first Pan-African Congress. The meeting was organized primarily by Henry Sylvester Williams, a Trinidadian barrister who coined the term “Pan-Africa” as a political response to the 1884 Berlin Conference where Europe carved up the African continent into colonial pieces.

Fighting genocide with solidarity, Du Bois closed the conference with an appeal for the “integrity and independence” of African states in “To the Nations of the World,” which included perhaps the most famous sentence in the Du Bois lexicon: “The problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color line.” This 1900 manifesto had a decidedly internationalist cast: for Du Bois, only a global analysis of the racial matrix could sketch out the full contours of the color line.

In 1905, Du Bois developed this analysis more fully after Japan defeated Russia in an inter-imperialist war over Manchuria:

The magic of the word “white” is already broken, and the Color Line in civilization has been crossed in modern times as it was in the great past. The awakening of the yellow races is certain. That the awakening of the brown and black races will follow in time, no unprejudiced student of history can doubt.

In 1903, Du Bois read an essay by the socialist leader Eugene Debs, “The Negro in the Class Struggle.” Du Bois chose to interpret a famous statement of Debs from that essay — “we have nothing special to offer the Negro, and we cannot make separate appeals to all the races” — as an affirmation of socialist universalism. Elsewhere in the essay Debs had written the following, sounding more like both Karl Marx and the “abolitionist” Du Bois to come:

Socialists should with pride proclaim their sympathy with and fealty to the black race, and if any there be who hesitate to avow themselves in the face of ignorant and unreasoning prejudice, they lack the true spirit of the slavery-destroying revolutionary movement.

Du Bois was now aligned, if temporarily, with the US socialist movement. In his 1907 essay “The Negro and Socialism,” Du Bois himself sounded like Debs: “We have been made tools of oppression against the workingman’s cause — the puppets and playthings of the idle rich.” The solution for him lay in a “larger ideal of human brotherhood, equality of opportunity and work not for wealth but for Weal.”

Du Bois made a “leap” from native radical to Pan-Africanist socialist in two hops. In 1912, he left the Socialist Party because of its failure, with the exception of Debs, to challenge Jim Crow in the American South. Then in 1914, World War I began. The Du Bois who had written “To the Nations of the World” fused his political training to produce one of his most important essays, “The African Roots of War,” published in Atlantic Monthly in May 1915.

Between 1917 and 1921, Du Bois sometimes unsteadily kept one foot in the Pan-African movement and one in the Russian Revolution. Writing in 1919 for the Crisis, Du Bois insisted that black labor in Africa and the South Seas “looms large” in “the problem of Equality of Humanity in the world as against white domination of black and brown and yellow serfs.” He railed against the “maledictions hurled at Bolshevism” by its enemies that had concealed what he saw as the “one new Idea of the World War”:

It is not the murder, the anarchy, the hate, which for years under Czar and Revolution have drenched this weary land, but it is the vision of great dreams that only those who work shall vote and rule.

In the same year, he took part in the first Pan-African Congress since 1900 with sixty representatives in Paris. The Congress passed a resolution calling for direct supervision of the colonies by the newly formed League of Nations to prevent their economic exploitation. In 1921, the Congress met in London and released a manifesto calling for an “international section in the Labor Bureau of the League of Nations, charged with the protection of native labor.” In 1923, a third Congress in Lisbon passed a similar resolution.

The Congress had a negligible influence on the League of Nations, which was far more committed to preserving colonialism than eradicating it. Indeed, the League famously created a “mandate” system that extended the reach of European rule, especially over the Middle East. This made the necessity of a stronger political response to capitalism clearer to Du Bois.

Between 1917 and 1921, Du Bois sometimes unsteadily kept one foot in the Pan-African movement and one in the Russian Revolution.

In 1926, he fatefully decided to travel to the Soviet Union. While in Moscow, he visited the Communist University for Eastern Peoples, which was attended by such figures as the future Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping, and the Chinese University, named after the Kuomintang founder Sun Yat-sen. He was struck by Soviet commitment to the education of national minorities, noting the faces of “Russians, Ukrainians, Jews, Tartars, Gypsies, Caucasians, Armenians and Chinese.”

Russia seems to me the only modern country where people are not more or less taught and encouraged to despise and look down on some group as a race . . . if what I have seen with my eyes and heard with my ears is Bolshevism, then I am a Bolshevik.

This carefully state-managed visit shielded Du Bois from the ongoing Stalinist counterrevolution whose consequences he seemed happy to ignore: “I know nothing of political prisoners, secret police and underground government.”

The Soviet trip hurled Du Bois permanently in the direction of Marxism. After his return, he studied Marx’s Capital and The Communist Manifesto. These readings were the basis of lectures he began at Atlanta University in 1932 on “Imperialism in the Sudan, 1400 to 1700,” “Economic History of the Negro,” and “Karl Marx and the Negro.” In 1933, he wrote that he wished to publish a series of articles in the Crisis intended to be a “rapproachement between black America and socialism” with topics like “The Class Struggle of the Black Proletariat and Bourgeoisie” and “The Dictatorship of the Black Proletariat.”

Readers of Du Bois will recognize these titles as the genesis for what became his masterwork, Black Reconstruction. Chapter 1 is titled “The Black Worker,” Chapter 10 “The Black Proletariat in South Carolina,” and Chapter 11 “The Black Proletariat in Mississippi and Louisiana.” Du Bois’s theory of the “general strike” of black labor — what he called in Black Reconstruction an “experiment of Marxism” — was his attempt at a “rapproachement between black America and socialism.”

However, readings of the book often miss the fact that Black Reconstruction was also a Pan-African text. For Du Bois, the most important aspect of the revolt against slavery was that it showed black American labor to be what Marx had called a “pivot” in the system of global capitalism. The black worker was representative, he wrote, of that dark and vast sea of human labor in China and India, the South Seas and all Africa . . . the great majority of mankind, on whose bent and broken backs today rest the founding stones of modern industry.

The lesson of abolition for Du Bois lay in its potential for world revolution:

Out of the exploitation of the dark proletariat comes the Surplus Value filched from human beasts which, in cultured lands, the Machine and harnessed Power veil and conceal. The emancipation of labor is the freeing of that basic majority of workers who are yellow, brown and black.

Du Bois’s Pan-African messaging was not lost on his revolutionary contemporaries. In 1938, the Trinidadian Trotskyist C. L. R. James published A History of Pan-African Revolt. The book referred to Du Bois’s Black Reconstruction as an engine for James’s own analysis of black slave revolts.

In The Black Jacobins, also published in 1938, James cited the example of self-organization by US slaves to underscore his own thesis that “Africans must win their own freedom.” As Robin D. G. Kelley has argued, much of James’s analysis is drawn directly from Black Reconstruction, “from his invocation of the ‘general strike’ to his description of the slaves’ hesitant responses toward the Union soldiers.”

Black Reconstruction was a turning point for Du Bois as a Pan-African socialist. Before he published the book, black radicals such as George Padmore had chided Du Bois for what they considered his petty-bourgeois orientation to socialism.

Padmore, a Trinidadian childhood friend of C. L. R. James, had joined the Communist Party of the United States in 1929. In 1930, he attended the Fourth Congress of the Profintern, or Red International of Labour Unions (RILU). The following year, the Profintern passed a “Special Resolution on Work amongst Negroes in the US and the Colonies.”

Padmore wrote to Du Bois seeking his support for a Negro World Unity Congress — an attempt to revive the dormant Pan-African movement. The invitation set the two men on a collaborative course that crested the wave of Pan-African socialism.

In October 1945, Du Bois and Padmore joined hands across the black Atlantic to lead the Manchester Pan-African Congress. Delegates unanimously voted for Du Bois as president of the Congress on its first day, and Padmore formally introduced him as the “father of Pan-Africanism.”

Delegates and associations taking part in the meeting included the Gold Coast Farmers Association, the Workers League of British Honduras, the Nigerian Trade Union Congress, and the Saint Lucia Seamen, Waterfront, and General Workers Union. A number of political organizations were also represented, from South Africa’s African National Congress to the People’s National Party of Jamaica, the Grenada Labor Party, and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

When he later commemorated the conference, the South African writer Peter Abrahams cited Du Bois’s 1940 book Dusk of Dawn as an inspiration for the goals of the Congress: “Century of the Common Man: Foreword to the Socialist United States of Africa! Long live Pan-Africanism!” Beyond the lofty rhetoric of Manchester, what did Pan-African socialism achieve?

Firstly, it launched the political careers of several anti-colonial activists who went on to lead Africa’s independence movements, including Ghana’s Nkrumah and Kenya’s Jomo Kenyatta, who helped organize the Manchester meeting. Secondly, it inspired a political current sometimes called “African socialism” which infused decolonization movements across Africa and the Caribbean.

In the final years before his death in 1963, Du Bois began to see Africa’s decolonizing and national liberation projects stalled, weighed down by the betrayals of national bourgeoisies, the unrelenting assault on the continent by racial capital, the differentiated national traumas of slavery, colonialism, and apartheid, the long history of European underdevelopment, and tensions between nationalist and internationalist theories of African liberation. Du Bois’s Pan-Africanist socialism at times fell back on sheer revolutionary hope:

With a mass of sick, hungry and ignorant people, led by ambitious young men, like those today supporting tribalism on the Gold Coast and Big Business in Liberia, under skies clouded by foreign investing vultures armed with atom bombs — in such a land, the primary fight is bound to be between private Capital and Socialism, and not between Nationalism and Communism. It may be in Africa, as it was in Russia, that Communism will prove the only feasible path to Socialism.

The most powerful legacy of Pan-African socialism is its original insistence that socialism and liberation struggles in particular nations cannot survive without challenges to racial capitalism at the global scale, and without the mass self-organizing of those Frantz Fanon called the wretched of the earth. For Du Bois, the concept of “abolition democracy” that he developed was not just a theory of black American freedom but one of international working-class emancipation. (IPA Service)

Courtesy: Jacobin Magazine

Jignesh Mevani Has Been A Consistent Fighter For Dalits In Gujarat

Jignesh Mevani Has Been A Consistent Fighter For Dalits In Gujarat