By Anjan Roy

From politicians to economists to the humble stock traders, nobody could really believe it will come to pass. Worse, in fact, it should be as bad as it turned out in reality.

Donald Trump’s promised April 2 announcement of tariffs on goods entering the United States turned out to be far worse than what was feared possible. At one stroke, Donald Trump has pushed America to a trade regime at least one hundred and twenty five years back. With its latest tariff rates, America would return to the same tariff regimes as in 1900.

Not even that. Philosophically, we have been thrown back to the days of the Mercantilists when the economic philosophers thought that imports were bad and exports good: thus, export all goods and import gold. We have been forced to migrate to a mindset dominant in the seventeenth century.

That was the gilded age of Mercantilism, epitomised by Jean Baptiste Colbert (1619-83). While reviewing a book on Colbert in 1940, Sir John Clapham had observed: Colbert had no single original idea and was “a big stupid man, tyrannical, brutal, fussy”.

By some eerie coincidence, this would appear very far apt description of 21st century’s most powerful and determining advocate of today’s modern sort of mercantilism.

Post April 2, America’s trade regime would be similar to what it was in 1900 and even earlier, when nations used to hide behind high tariff walls. And with that one stroke of April 2, Trump has dismantled the entire structure of world trade and economic relations among nations which was built so carefully over the years since the second World War.

The World Trade Organisation might just as well be formally scrapped. Dispute settlement bodies for resolving trade-related differences among nations stands outmoded. There is no point registering grievances. If the most powerful economy in the world can pose tariffs at will on countries, where is the rules based trading system, based on the cardinal principle of most favoured nation treatment.

Leaving aside the broader questions global trade regime, for one, what happens to India post April 2? Nothing too grave generally. Some sectors which had exposure to America would certainly be hurt, but generally economy wide India should be well-cushioned.

Firstly, India’s overall exposure to global trade is not high. On top of it, exports to America account for just 2.2% of India’s GDP. If a fraction of that is hit, the incidence could be easily manageable.

The impact of Trump tariffs has to be seen in comparison to others. The world is not a “absolute” place, it is a “relative” place. For example, the incidence of Trump tariffs on Indian exports would be an average of 26%, while those from China would be 54%, according to expert calculations, taking into account the earlier imposition of some tariffs.

Thus, the Indian exports would be hit less than half as much as these would impact Chinese exports to USA. With effort, Indian exporters could still work to contain costs and seek to minimise the impact of the latest tariffs. But for China, it would be a far harder job.

Secondly, China is far more dependent on exports to the United States than India. As such, the Indian economy is, as is well known, driven by domestic demand, while the Chinese is abjectly dependent on exports. China, for example, has capacity to produce steel double its domestic requirements. Hence, for the survival of the Chinese steel industry, it has to export.

Some countries are even more vulnerable, given their dependence on exports of some select items. To cite an example near at home, Bangladesh had also been subjected to tariffs which had so far been minimal or totally exempted. Given the dependence of Bangladesh on garment exports, and more so to America, the country’s economy would face a very difficult situation with a 34% tariff.

Some experts now feel that at least in three areas India exports to US might benefit. Noted agricultural economist Ashok Gulati feels that given the tariff structure across farm sector, Indian producers enjoy some clear advantages and farm exports to US could even rise.

Secondly, pharmaceutical exporters feel buoyant. The tariffs have left the drugs industry alone. A good deal of Indian drugs are consumed in the United States and these have been kept outside the purview of present tariffs. With clear cost advantages, Indian drugs industry enjoys competitive advantages.

Thirdly, some segments of garments and telecommunications exports could gain competitive advantages as rival countries have been slapped with larger rates of duties. China and Vietnam are for example now subjected to far higher duties. Besides, India could as well ramp up its manufacturing with the PLI schemes which can become cost effective when compared with rival products. It is not as if America would altogether stop import all goods.

As the world adjusts to the Trump tariffs, there would be unforeseen consequences. Countries would face serious economic upheavals. Some will see new opportunities. Global trade had undoubtedly given rise to unprecedented development and growth. Many of these impulses would vanish and it could just as well be an era of bigger thy neighbour approach.

In this new world of uncertainty, India would surely one of the most stable and self-reliant. Based on Nomura’s recent findings, India stands as one of Asia’s most resilient economies in the ongoing trade conflict and economic adjustment. (IPA Service)

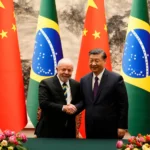

Brazilian President Seeking Support From China And Russia To Meet Trump’s Threat

Brazilian President Seeking Support From China And Russia To Meet Trump’s Threat