By Krishna Jha

It was in the decade of 1840s, dominated by strikes and struggles and signified by upheavals and uprisings. Among them the most popular but brutally suppressed one that remained alive only for four days – but has kept echoing even after almost two centuries — was the June uprising. It was in Paris. The tensions between bourgeoisie and the workers were most intense here. By February 1848, there was the transition and a new society started emerging, divided in two streams.

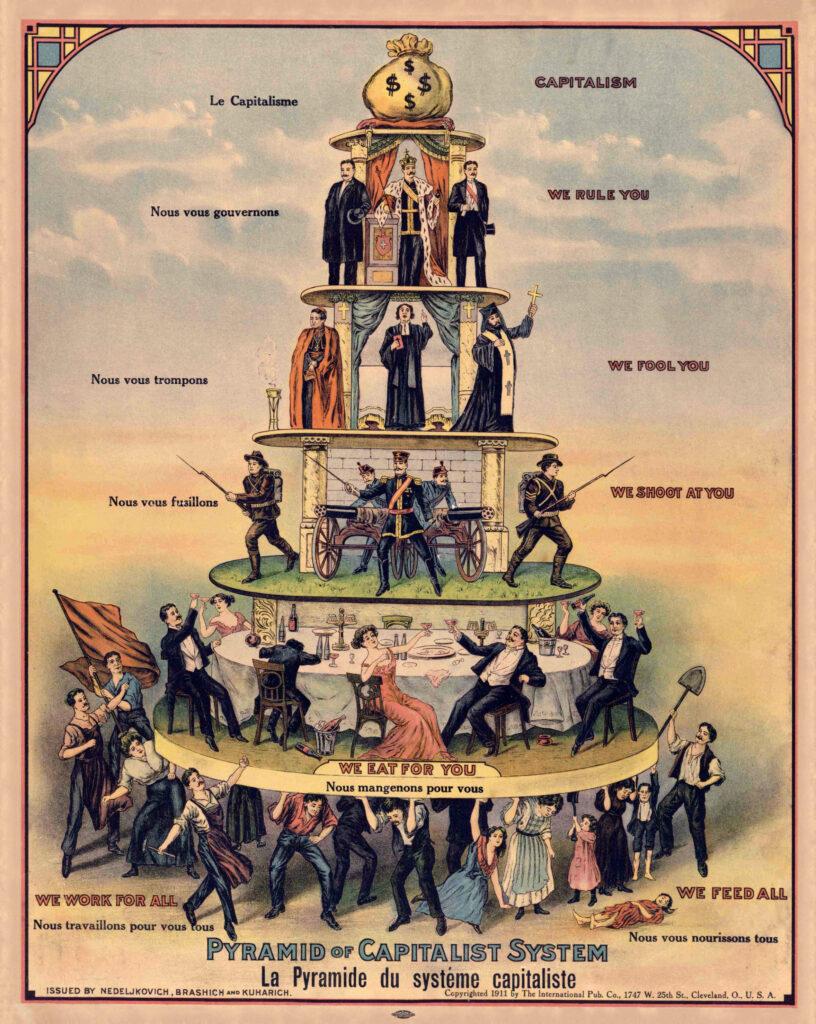

One of them spent its labour power to produce commodities, that met the needs of the human want. The other was the owner who organized the production, with raw material, means of production, which in those days were looms, or primitive machines, huge and small both run with fuel or driven by horses. Steam power was discovered and its utility spread out in different kinds of machines, to produce and transport both. Gaining from paying less and buying the labour power at a cost that was cheaper than the cost of the products that were created by the labourer himself.

The days were unusual. It was a time when the entire superstructure was crumbling along with the agrarian system and the blind feudal rule. Kings were no more divinities. However there was one glaring and consistent factor and that was constant and all pervasive. It was the absence of food, and rule of hunger suffered by the larger masses. So far as the new government was concerned, it was content to recycle the slogans and symbols of the great 1789 French Revolution, proclaiming liberty, equality, fraternity, and flying the tricolour flag. They had lost all faith for the royalties.

People were angry and devastatingly hungry. Another howling factor was bankruptcy, hovering over France. The situation was getting volatile. Slowly coming to the sight were the outlines of new society, with new thinking. There was growing need for democracy and representative government. France was not alone in shaping the idea of democracy, with individual rights, equality. They were waiting for a new dawn. It was the rule of capital identified by not only France, but also in other countries. The results were amazing, though not unexpected.

It was industrial age that was getting ushered in, with new machines, and a democratic set up to rule over. During the 1830s and 1840s, socialist and communist ideas and organisations had proliferated with the expansion of the city’s working class. These groups were interested in achieving working-class emancipation, which would mean going beyond the traditions of 1789. It was in 1848, in its beginning itself, when Karl Marx and Frederick Engels had just got over the writing of the Communist Manifesto when a series of revolutions broke out in the European continent. These were not the communist revolutions, instead they were revolutions for liberal reforms against old European autocracies.

Marx and Engels had thrown themselves into the revolutionary movement, taking part in the democratic struggle in Cologne. On 1 June 1848, they launched a newspaper under Marx’s editorship, the Neue Rheinische Zeitung, with the subtitle ‘Organ of Democracy’.

In 1848, France was in the middle of an economic depression with high unemployment. In the February revolution, armed workers demanded that the new government commit to the ‘right to work’, specifically to guarantee the welfare of the working class. This was only ever grudgingly conceded. The government set up national workshops for the unemployed, but these offered sporadic, low-paid work which was menial, monotonous and resented by the unemployed skilled artisans of Paris.

On June 22, the government terminated the national workshops, telling the workers who had enrolled in them that they would instead have to enlist in the army or be deported from Paris to work elsewhere.

That evening, workers began to build barricades. The June Days uprising had begun. From the moment they received news of the uprising, Marx and Engels supported the revolutionaries. This was an exceptional position to take; by contrast with the earlier wave of revolutions, the June insurrection had hardly any prominent defenders. As a result of their stance, the Neue Rheinische Zeitung lost all its remaining shareholders. When the publication closed down the following year as the counter-revolution gained ground, Marx had the final edition defiantly printed entirely in red ink. These red words proclaimed that the June insurrection was ‘the essence of our paper’.

Marx and Engels were able to gain information about what was happening in Paris from two of their journalists who were based in France: Sebastian Seiler, who worked as a stenographer in the French National Assembly, and Hermann Ewerbeck, a doctor who treated the wounded revolutionaries and reported what they were telling him.

In The Communist Manifesto, Marx and Engels wrote: ‘The proletariat, the lowest stratum of our present society, cannot stir, cannot raise itself up, without the whole super incumbent strata of official society being sprung into the air.’

They were describing the way in which working-class revolution would necessitate a complete break with the old society. The truth of this was confirmed by the experience of the June Days which, as Ewerbeck told them, was very quiet compared to the February revolution: the barricade fighters in June were not singing songs about 1789.

This was why Marx characterised the February revolution as the nice revolution, when the class divisions in society were denied, obscured by the universalist rhetoric of brotherhood. June, by contrast, was the ugly revolution because it made those class divisions appallingly visible. The new French government went to war with the workers on the barricades: it called up the army.

Marx and Engels emphasised the scale of the violence employed against the June insurgents. It revealed the lengths to which a frightened bourgeoisie would go to safeguard their power.

In 1919, after a failed workers’ uprising, the revolutionary Rosa Luxemburg wrote her last article hours before her murder by the proto-fascist Freikorps. She titled it ‘Order reigns in Berlin’. That was a reference to Marx’s article on the June Days, which recalled that the French government, like other repressive regimes, slaughtered in the name of ‘order’.

It was only partly a satirical point. Marx, and later Rosa Luxemburg, were also making the point that fundamentally the bourgeois social order was based on violence and subjugation. That was why they dedicated their lives to overthrowing it. (IPA Service)

Bihar Congress Organisational Meeting Revealed Fissures Over Dalits Issue

Bihar Congress Organisational Meeting Revealed Fissures Over Dalits Issue