By Dr. Gyan Pathak

Prime Minister Narendra Modi Government has been in the habit of changing definitions to show sudden growth in various sectors of economy without actual growth on the ground. We have seen it in the past how change of status of certain state highways to national highways suddenly pushed up the length of the national highway under Modi government without constructing them. The latest such example has come in the MSME sector.

In the document titled “Enhancing MSMEs Competitiveness in India” by NITI Aayog, which is chaired by Prime Minister, the Vice President Suman K Berry lauded the growth of MSMEs in the country contributing to India’s economic growth, and consistently contributing to job creation, manufacturing and exports.

“In recent years, its significance has only strengthened. The share of MSMEs in India’s Gross Value Added (GVA) has steadily increased from 27.3 per cent in 2020-21 to 29.6 per cent in 2021-22, reaching 30.1 per cent in 2022-23,” he said in his message, adding, “Exports from MSMEs have also seen substantial growth, climbing from Rs3.95 lakh crore in 2020-21 to Rs12.39 lakh crore in 2024-25. Moreover, the number of MSMEs engaged in export activities has surged, rising from 52,849 in 2020-21 to 1,73,350 in 2024-25.” Berry also praised the Union Budget 2025-26 for the government’s bold steps mentioning various key initiatives including raising investment and turnover limits for MSME classification.

However, his comparison of the data is wrong and deceptive, since the current data with new definition is compared with the old data and definition. It should be recalled that Modi government had changed the definition of MSMEs in Atmanirbhar Bharat Package launched during the COVID-19 lockdowns and containment measures from July 1, 2020. Definitions were changed after 14 years of MSME Development Act came into existence in 2006.

In 2019-20, as per the definitions, a manufacturing enterprise was Micro if it had less than Rs25 lakh investment in plant machinery, small if between Rs25 lakh and Rs 5 crore, and medium between Rs5 crore and Rs 10 crore. For service sector MSMEs, these were less than Rs10 lakh, between Rs10 lakh to Rs 2 crore, and between Rs2 crore and Rs 5 crore. The Gross Value Added (GVA) by MSMEs in India’s GDP was 29.7% in 2017-18, rising to 30.5% in both 2018-19 and 2019-20. There was clear stagnation in growth of MSMEs. MSMEs contributed 49.75% to India’s exports in 2019-20. With total shutdown of the economy, MSMEs of the country was experiencing extreme disruption which had impacted availability of jobs.

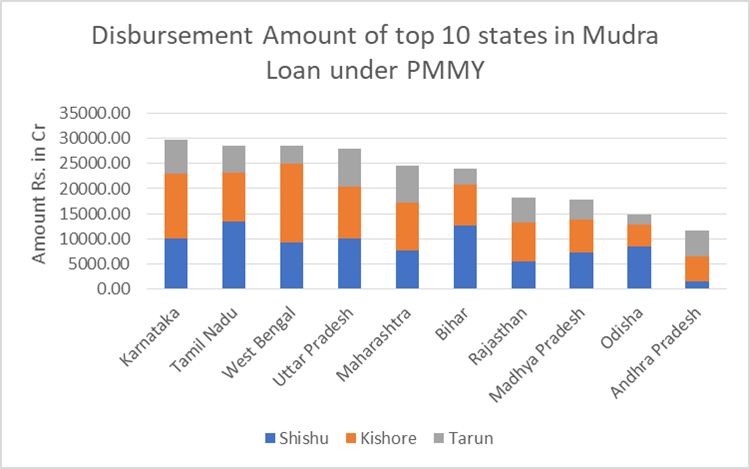

What did the Atmanirbhar Bharat Packaged did for the MSME sector? It changed the definition to show a rosy picture of the central government’s performance under PM Narendra Modi, apart from announcing many incentives for the MSME sector, including collateral free loans, that were very slow in sanctions and disbursements, which little helped this sector, as the data shows.

Under the new definition in 2020-21, separate definitions for manufacturing and service enterprises were merged. The investment limits were increased from Rs 25 lakh to Rs 1 crore for micro enterprises, from Rs 5 crore to Rs 10 crore for small enterprises, and from Rs 10 crore to Rs 20 crore for medium enterprises. A new criteria of annual turnover was also introduced. The turnover limit for Micro, Small and Medium enterprises were set to Rs 5 crore, Rs 50 crore, and Rs 100 crore, respectively.

The change of definition suddenly increased the number of MSMEs because it brought the bigger enterprises into MSMEs, which helped the government to show that despite COVID-19 crisis, shutdowns and containment measures the MSME sector sustained a contribution in the India’s GDP at 27.3 per cent. Had the government not changed this definition MSMEs under old definition would have much reduced contribution due to total disruption. It was under new definition by including bigger enterprises in the MSME categories, the sector’s contribution in GDP (GVA) increased to 29.6% in 2021-22 and reaching 30.1% in 2022-23.In no way it was a big deal, since even under old definition MSMEs contribution to GDP (GVA) in 2018-19 and 2019-20 was 30.5 per cent.

The figures thus camouflage the reality that in actuality MSMEs did not perform well even after bringing in bigger enterprises under MSMEs. The older and smaller MSME enterprises were actually struggling for survival, and the frightening reality was veiled by bringing the bigger enterprises into MSME categories to show a collective rosy picture.

Even under the old definitions smaller MSMEs contributed 49.75 per cent to India’s exports in 2019-20. By change of definition, bringing bigger enterprises was expected to considerably increase this contribution. However, it decreasing to 49.35% in 2020-21 and 45.03% in 2021-22. The share further declined to 43.59% in 2022-23 but recovered to 45.73% in 2023-24, with 45.79% recorded up to May 2024 (the latest data available in the Union Budget 2025-26).It is still less than the contribution of old definition of smaller MSMEs by almost 4 percentage point. It shows that bringing bigger enterprises into MSME category has not really benefited, but to coverup the struggle of survival of the older and smaller MSMEs.

Look at how NITI Aayog vice president Berry praises the Modi government despite the figures give clear impression of failure of the Centre in reviving the MSME sector. He says, “Exports from MSMEs have also seen substantial growth, climbing from Rs 3.95 lakh crore in 2020-21 to Rs 12.39 lakh crore in 2024-25.”

The game of change of definition still continues. The Union Budget 2025-26. The investment limits were increased from Rs 1 crore to Rs 2.5 crore for micro enterprises, from Rs 10 crore to Rs 25 crore for small enterprises, and Rs 50 crore to Rs 125 crore for medium enterprises. Similarly, turnover limits have been increased from Rs 5 crore to 10 crore, Rs 50 crore to Rs 100 crore, and Rs 250 crore to Rs 500 crore respectively. The definition may even bring bigger enterprises into the MSME sector. It may improve the overall data to show significant growth on the paper but the real MSME’s struggle for survival would continue, thereby the government would fail in generating large number of new jobs.

Nevertheless, the document “Enhancing MSMEs Competitiveness in India” delves into the array of challenges confronting MSMEs – ranging from financial constraints and technological gaps to skill shortages and regulatory hurdles. Overcoming these challenges is pivotal for creating an environment where MSMEs can thrive and compete effectively, it says in the first chapter.

The second chapter introduces a competitiveness framework rooted in cluster theory. By leveraging these clusters, MSMEs can enhance efficiency, spur innovation, and respond more adeptly to market demands, thus gaining a competitive edge.

The third chapter takes data from Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) that indicated 74.3 per cent of workers engaged in proprietary and partnership enterprises are involved in non-agriculture sector. It shows the dominance of informal sector. In addition, the UDYAM portal data reveals that a significant proportion, specifically 81 per cent, of MSMEs operate as proprietorships, with 80 per cent falling into the Microenterprise category. Recognising the prevalence of such ownership structures, it becomes crucial to analyse and assess the performance of these enterprises collectively, which the cluster approach facilitates.

The final and fourth chapter reviews the policy landscape governing MSMEs at national and state level, evaluating the effectiveness of current measures aimed at bolstering competitiveness. It reveals that despite numerous policies, gaps in awareness, stakeholder engagement, and adaptability limit their impact. The chapter concludes with recommendations for a more robust, adaptive policy framework that responds to the evolving needs of MSMEs, emphasizing continuous monitoring, feedback integration, and data-driven adjustments. (IPA Service)

After Strikes On Pak Terror Camps, India Has To Put More Political And Diplomatic Pressure On Islamabad

After Strikes On Pak Terror Camps, India Has To Put More Political And Diplomatic Pressure On Islamabad