By Rishika & Raj Krishna

“The Good Governor should have a broken leg and keep at home.” — Miguel de Cervantes

Miguel de Cervantes’s words best capture a governor’s expected role within a parliamentary democracy. The governor’s primary duties are consultation, encouragement, and advice. It is also expected that he remains above provincial politics.

Due to the conduct of the Governors of certain Indian states, it certainly seems that the Constitution’s values, morals, and ethos have been compromised. Across opposition ruled states, Governors and Chief Ministers, in recent years, have entered into loggerheads over legislative issues. Resultantly, the State’s administration has suffered.

The Chief Minister and his Cabinet are chosen and elected by the voters of the state. However, despite being a President appointee the Governor still has a significant role in the polity of the state. Consequently, it is imperative that a standoff between the two be settled quickly.

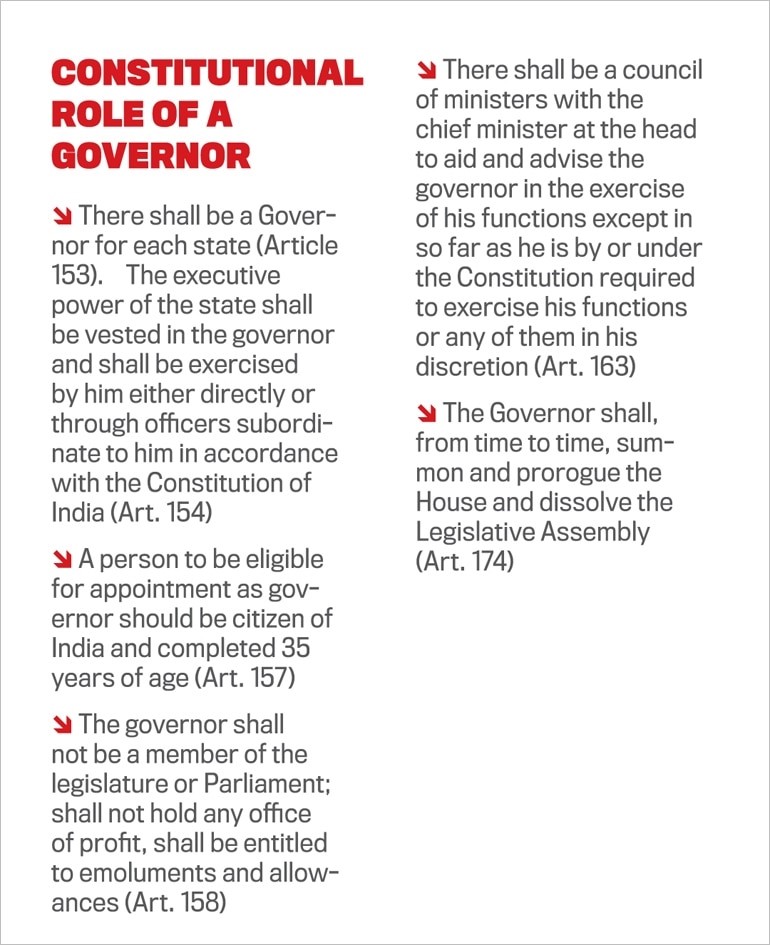

The Governor is assigned the executive responsibility of the State under Article 154 of the Constitution. However, Article 163 of the Constitution clearly states that the Governor should consult the Chief Minister and his Cabinet before taking any decision. It is only in certain exceptional circumstances that the Governor can exercise discretionary powers. The Constitution clearly lays out the conditions for these discretionary powers to be exercised. Thus, it is not an absolute, but a limited form of discretionary power. In most cases, he is limited by the support and counsel of the Chief Minister and his Cabinet. But this is not happening any – that is the truly concerning aspect.

The Tamil Nadu Governor is currently facing a lawsuit in the Supreme Court for withholding assent to several Bills passed by the Tamil Nadu state legislature. After four days of hearings this month, the Supreme Court reserved judgement on February 11, 2025, in a high-stakes decision which would decide how Article 200 is interpreted. Article 200 addresses the governor’s authority to refuse assent to laws.

Notably, Article 200 is silent on whether the governor must act on the bills within a certain amount of time or if he must consent to them at his own discretion. Article 200 of the Constitution states that the Governor must either announce his or her assent to the bill, withhold his or her assent, or reserve the bill for the President’s consideration. It does not designate a certain time frame for the governor’s consent or specifically allocate this responsibility to his discretionary powers.

A number of commissions, including the Puncchi Commission and the National Commission to Review the Working of the Constitution, have recommended incorporating constitutional amendments providing for a timeframe in which the Governor has to decide whether to withhold his assent to the bill or not. Yet, nothing has been done to implement these suggestions. When legislative action fails, the judiciary must step in and establish guidelines to guarantee the governor’s assent of the bill.

Recently, in State of Punjab v. Principal Secretary to the Governor of Punjab (2023), the Supreme Court ruled that, under the Cabinet System of Government outlined in our Constitution, the Governor is the constitutional head of the State and performs all of the duties and powers granted to him by the Constitution with the assistance of his Council of Ministers, with the exception of those circumstances under which the Constitution requires the Governor to perform the duties at his/her own discretion.

A key feature of the English political system is that the Ministers are foremostly accountable for executive actions, not the monarch. The practical requirement that the Crown must find advisors to take accountability for his actions limits the sovereign’s authority. Interestingly, the Indian Constitution also contains this rule of constitutional law. Instead of a presidential system, the Indian Constitution calls for a responsible, parliamentary system of governance at both federal and provincial level. As the head of state under the constitution, the governor has the same authority.

In Principal Secretary to the Governor of Punjab, the Supreme Court emphasized that if the spirit of Article 200 were to be negated, the Governor, as the unelected head of state, would have the authority to essentially veto the legislative branch’s operations by a duly elected legislature by merely stating that assent is withheld with no other options. A constitutional democracy founded on a parliamentary system of government would be incompatible with such a course of action.

Justice D.Y. Chandrachud, in Principal Secretary to the Governor of Punjab further noted that the substantive part of Article 200 empowers the Governor to withhold assent. However, in cases wherein the Governor refuses to give assent to the bill then he is supposed to inform the State Legislature of his decision as early as possible. As a Constitutional Head of the State, the Governor can recommend reconsideration of the entire Bill or any part thereof, and even indicate the desirability of introducing amendments. However, the legislature alone has the last say over whether or not to abide by the governor’s advice. According to the Court, the way the Governor fulfills his or her duty as a symbolic head of state is essential to preserving federalism, which has been deemed to be a fundamental component of our Constitution. It was further stated that exercising unrestricted discretion in areas not beyond the governor’s purview runs the risk of interfering with the operations of the state’s democratically elected government. Lastly the Supreme Court also emphasized upon the need of cooperation between the offices of Chief Minister and Governor in a representative democracy.

Despite the Court’s landmark ruling, Governors in opposition ruled states continue to act in impartial manners. Amending the Constitution may be the best way to address this burning issue. However, until that happens, detailed guidelines from the Supreme Court regarding the interpretation of Article 200 would greatly mitigate instances of indefinite pendency of bills. The Court while issuing directives must consider a number of factors, like the governor’s workload, the time period for which the bill is pending, and also the governor’s justifications for withholding his assent. It is important that the scope of discretion is restricted, and even within this restricted scope, his decision should not seem capricious or extravagant.

An intrinsic feature of constitutions is their silences and abeyances. Constitutional silences are necessary, intentional, and implicit. They are included in the text but never specifically stated. However, the silences have routinely resulted in situations of ‘Constitutional Hardball’ .First used by Mark Tushnet in a 2004 essay, the phrase ‘Constitutional Hardball’ refers to how political actors take advantage of laws and processes to further their own agendas. These actors transgress the country’s established norms, practices, and conventions in the process. Given that it subverts democratic principles, constitutional hardball is therefore seen as a threat to democracy by a number of legal scholars.

Looking closely today, we can see ample evidence of constitutional hardball in Indian polity. The question that now emerges is what is in store for us. In U.N. Rao v. Indira Gandhi (1971), the Supreme Court ruled that provisions of the Constitution are inspired by the British Conventions. If we ignore British practices, we may run the risk of misinterpreting the articles of our Constitution. Thus, it could be said that the Indian Constitution is heavily reliant on conventions.

In ‘The Indian Constitution: Cornerstone of a Nation,’ constitutional law scholar Granville Austin points out that the founders of the Indian Constitution contemplated making specific British conventions as explicit clauses. Later on, however, they felt that political actors of the day would inevitably abide by norms and customs established by the Constitution. Unfortunately, by ignoring the established constitutional conventions, the politicians and leaders of the day have failed the framers. Incorporating the conventions into our Constitution is imperative. (IPA Service)

Courtesy: The Leaflet

Mayawati Is Apprehensive At Her Nephew Akash Anand’s Personal Popularity

Mayawati Is Apprehensive At Her Nephew Akash Anand’s Personal Popularity