By Dr. Gyan Pathak

Though India has emerged as an important start-up hub of the world, its ecosystem density is below potential, and is now facing a funding slowdown compared to other global hubs that became sharper in 2023. Funding slowed down by 65 per cent for the country compared to a year before in 2022.

The latest OECD report on “Start-up Asia” said that drop in funding were observed worldwide as interest rates crept up to reduce inflationary pressures and reflecting higher perceived geopolitical risks. Data for 2023 show a decline of 40 per cent in even the United States.

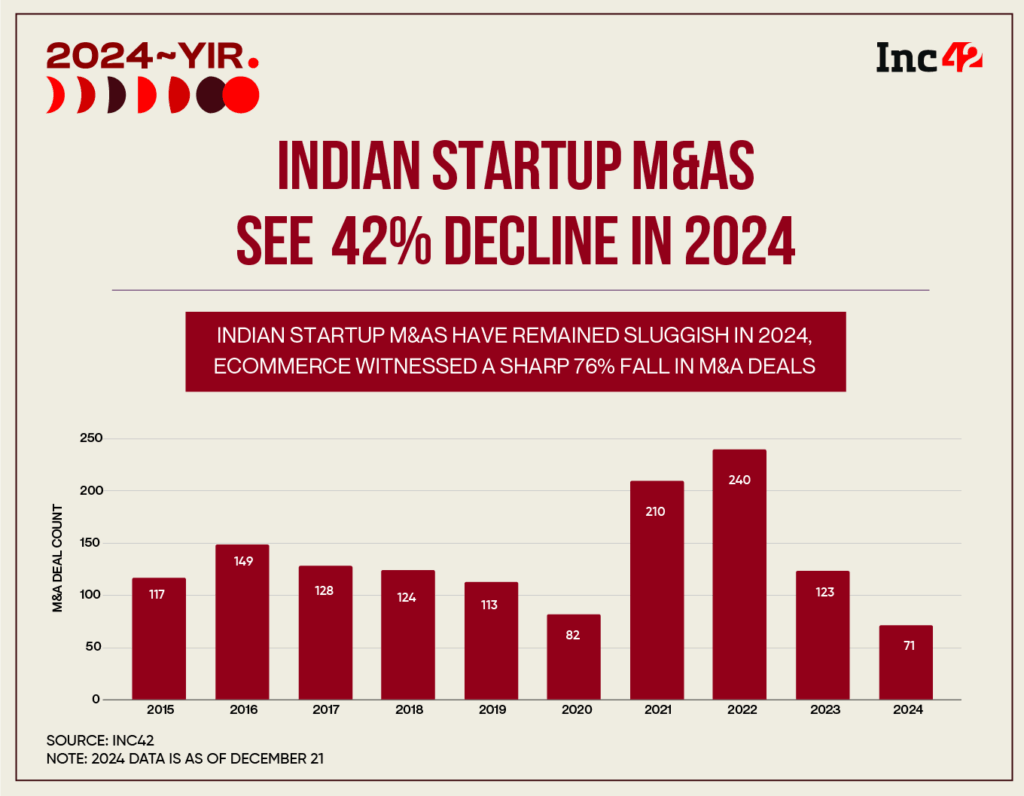

The larger decline in India is explained by the role of unicorns in total financing in India – the current shortage of capital and the preference of global investors to reduce risk affects larger and later stage deals more, like the ones that involve unicorns. In line with trends in other hubs in Asia, this funding “winter” is contributing to a re-balancing of the start-up ecosystem towards smaller valuations and an emphasis on profitability. Preliminary data for 2024, show a trend towards recovery, although still below the peak of 2021.

India launched start-up India in 2016, and was actually designed to revitalize the country’s start-ups, which had already been developing since the 1990s, building on India’s strength as a software centre. India’s start-ups have captured world attention, as the country represents one of the largest and most populous markets in the world, and has showcased a growing capacity for innovation, particularly in digital technologies.

India is the second largest start-up hub in the world (9% of world’s start-ups) after the United States (32%)and Asia’s largest one (45% of Asian total in 2021-23). India is also one of the oldest start-up ecosystems in Asia, with several start-ups born in the margins of the country’s large IT sector attracting large investments already in the 2000s, such as OnMobile, a gaming spin-off of InfoSys founded in 2000.

However, growth was not linear. The burst of the dotcom bubble cooled down investor interest globally in internet-related ventures, and it would be another decade before investments started accelerating and surpassing the USD 1 billion mark. Around this time, several of India’s early unicorns started appearing, such as Flipkart, an e-commerce giant and InMobi, an ad-tech firm, both established in 2007, and acquiring unicorn status in 2011-2012.

However, presently, despite its large size, the ecosystem’s density is still below potential. In India, there are about 4 start-ups per 100 000 people, which compares well to the Asian average (3) but is a long way one from the OECD (42) and the United States (76).

The country accounts for about 5% of global venture capital (VC) investments, fourth highest after United States (48%), China (14%) and the United Kingdom (5.5%), and second highest in Asia (2021-23). India’s VC scene is also large with respect to the local economy: VC accounted for 0.62% of GDP in India in 2021-23, the second highest in Asia after Singapore (1.54%), and close to the United States (0.79%). This makes India stand out compared to newcomers in Asia, such as Thailand, Malaysia and the Philippines, whose VC investments have grown fast during the past decade, but account for around six times less, at around 0.1% of GDP.

The country is home to47 unicorns (defined in this report as firms valued at over USD 1 billion and created between 2014 and2023), the fourth largest number after the United States, China and the European Union.

Nevertheless, the Government of India had said on January 16, 2025 when India marked nine years of Startup India, that there were over 100 unicorns. The current OECD report covers the period until 2023, with warning of several risks, which should be a matter of great concern.

Unicorns in India are diverse in terms of sectors, with the majority of India’s concentrated in the consumer and retail sector (36%), fintech (24%) and industrial (19%) areas. Among the more highly valued unicorns are new digital payments firms such as Razorpay, CRED and BharatPe, e-commerce / food delivery platforms such as Swiggy, and manufacturers such as electric scooter maker Ola Electric.

Delhi, Bengaluru and Mumbai stand out as the country’s largest and most mature hubs, accounting for51% of Indian start-ups. However, growth in start-up ecosystems has spread well beyond these.

About12 of India’s cities are among Asia’s thirty largest start-up hubs, with Delhi the largest one in the region followed by Tokyo, Singapore, Bengaluru, Seoul, Mumbai and Beijing. India’s relatively dispersed start-up geography is characteristic of large economies that have developed multiple poles beyond the capital city. For instance, in the United States, the top three hubs (Silicon Valley, New York and Los Angeles) account for 33% of the total, a smaller concentration than in India, while in China for56%, about the same as India. By contrast, in most countries the capital city dominates, as for instance in Korea (85%), Japan (76%) and Indonesia (71%).

As India’s larger hubs become increasingly crowded and cost pressures mount, as emerging technologies grow ever more diffuse, and with the support of local public policies, new hubs are emerging in India, such as Pune, Hyderabad (6% of India’s start-ups each), Chennai and Ahmedabad (4% respectively).

National investors account for the majority of deals, while foreign investors provide the bulk of financing. About 77% of venture deals during 2020-22 had participation by a local investor, either on their own (40.4%) or together with a foreign investor (36%). However, foreign investors account for the majority of the funding in India, with as much as 75%according to some estimates, as they are particularly active in funding the latestage, larger deals. Corporate venture capital accounts for a relatively low share of overall deals, about 7%.

Despite the increasing density of the investor ecosystem, access to sizeable finance, particularly at the seed stage, remains an obstacle for start-ups in India. The share of seed deals in India stands at 72%, in line with the OECD average (75%) and Asian one (67%), but the share of financing that these deals receive is significantly lower, at 6% of total, half that in Asia (13%) and three times less than in OECD (19%).

Similarly, early-stage deals are relatively numerous (18% of total, compared to 20% in OECD on average), but they receive about half the financing that they do on average in Asia and OECD.

The top sectors by share of total VC funding in India in 2021-23 were fintech (22%), e-commerce (12%),transportation and logistics and IT and software (11% each). The top sectors for start-ups in India are IT (25% of all start-ups), business services (12%) and sales and marketing (8%).

As of February 2024, 31 of the 36 Indian states and union territories (UTs) have their own start-up policies, apart from the Union Government’s. The policies are co-ordinated under the umbrella of the Start-up India Programme. However, given the risks and bottlenecks, the OECD report has suggested updating the policy mix. Stronger linkages with the scientific base, opportunities to experiment and a mature quality infrastructure and intellectual property system are also needed.

The OECD report strongly recommends strengthening image and reputation, mentioning that Indian start-ups sometimes suffer from reputational issues, linked to a perceived lower quality when it comes to new technologies. (IPA Service)

Well-Curated Myth Of Modi’s Friendship With Trump Explodes Like A Cluster Bomb

Well-Curated Myth Of Modi’s Friendship With Trump Explodes Like A Cluster Bomb