By Dr. Gyan Pathak

The Era of Joblessness that begun with Prime Minister Narendra Modi assuming second term in 2019, has been worsening with pace of regular job creation substantially decreasing. Coupled with high prices and inflation, the situation pushed people in unprecedented economic distress that led rise in self-employment rather than the so-called economic growth that the government has been boasting about.

The most recent study, the “State of Working India 2023” by Azim Premji University, says that the pace of regular wage jobs creation has decreased due to the growth slowdown and the pandemic. The gender-based earning disparities have been stagnated since 2017 when women were earning 76 per cent as wage in comparison to men workers.

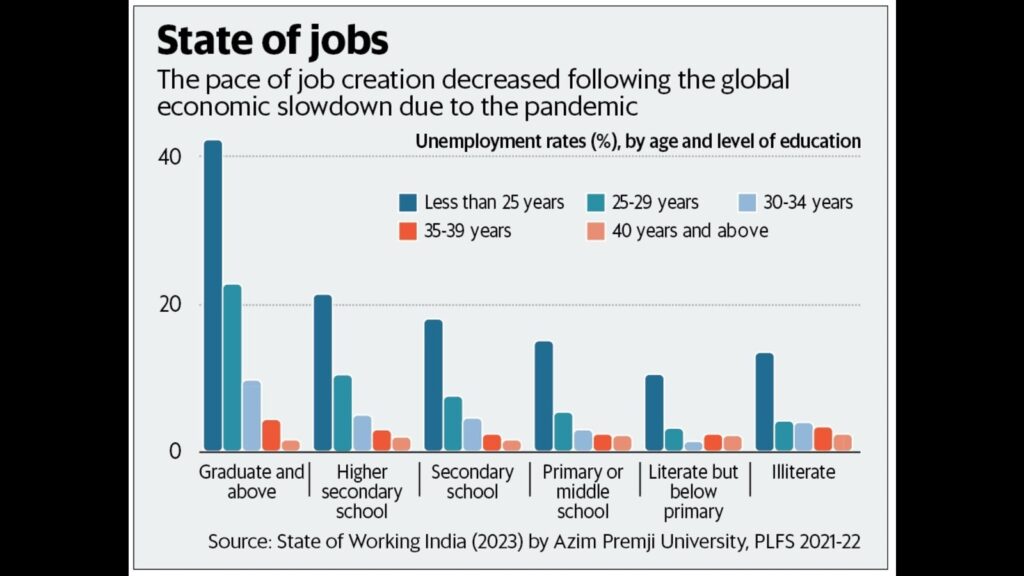

Connection between growth and good jobs remain weak, the study found, suggesting that “policies promoting faster growth need not promote faster job creation.” Decent employment growth was faster between 2004 and 2019, as also share of workers with regular wage or salaried work, which grew from 18 per cent to 25 per cent for men and 10 to 25 per cent for women. However, since 2019, both has plummeted to 20 per cent for women. Post-Covid, Unemployment rate remains above 15 per cent for graduates and more worrying it touches a huge 42 per cent for graduates under 25.

After falling or being stagnant since 2004, female employment rates (Women’s Participation Rate or WPR is short) have risen since 2019, but for the wrong reasons. Since 2019, the increase in rate was due to rise in self-employment which was led by economic distress, not by the economic growth. Before COVID, 50 per cent of women were self-employed. After COVID this rose to 60 per cent. As a result, earnings from self-employment declined in real terms over this period. Even two years after the 2020 lockdown, self-employment earnings were only 85 per cent of what they were in the April-June 2019 quarter.

The study has found the SC and ST entrepreneurships are still rare. SC and ST owners of enterprises are barely represented among firms employing more than 20 workers. Correspondingly, upper caste overrepresentation increases with firm size.

Before 2019, economic growth pulled people out of agriculture and the share of regular salaried workers rose. But women left the workforce and informality levels remain a concern. Although share of non-agricultural employment rose, it was not matched by a similar increase in the share of regular wage employment or employment in the organised sector.

The caste analysis shows that SC workers are far more likely to be in casual employment compared to others. As of 2021-22, around 22 per cent of SC workers were regular wage as compared to 32 per cent of others. However, 40 per cent of SC workers were in casual employment as compared to only 13 per cent for others. SC workers have been increasingly moving from agriculture into construction, which has remained the principal source of casual work.

The employment structure varies far more across gender and caste identities than it does across religion, the study says. It is worth nothing that Muslims are less likely to hold regular wage jobs and more likely to be in own-account or casual wage work over the entire four-decade period after controlling for education, household size, state and other relevant factors. It may be recalled that persistent under-representation in regular wage work was noted in the Sachar Committee Report of 2006. It continues to be a matter of concern, the study emphasized.

In non-farm sector in India, output consistently grew much faster than employment, which resulted into steady fall in the employment elasticity, which is far lower than the developing country average. The most recent period (2017-2021) is an exception to the trend. Growth significantly slowed down but employment rose sharply. The study concluded on the basis of this government data that growth and employment have been uncorrelated. However, other sources suspect the data itself and question – how can employment rise when economic growth slows down? Yes, it can happen due to faulty way of counting employment and unemployment in the country.

Unemployment scenario is disturbing for educated youth, the study has pointed out, though it is still high among all below 25 years of age. Quoting the government PLFS data for 2021-22, the study highlighted the unemployment rate among illiterate at 13.5 per cent, literate but below primary 10.6, Primary or middle 15, secondary 18.1, higher secondary 21.4 and graduate and above 42.3 per cent. For youth between 25 and 29 years of age unemployment among higher secondary was at 10.6 and among graduates and above was 22.8 per cent. Even at age between 30 and 34, unemployment among graduates and above was as high as 9.8 per cent.

The study raises a pertinent question while pointing out that graduates eventually find jobs, but what is the nature of jobs they find and do these match their skills and aspirations? More research is needed on this important topic, the study suggests.

Majority of women still remain outside the workforce in India due to supply and demand side challenges, the study pointed out. Female LFPR in almost all states of the country lie below the line of best fit, which meant female LFPRs are lower than predicted for their level of per capita GDP. Even if gender norms change and are no longer a barrier for women to undertake paid work, there still remains the question – are there enough jobs? The study finds several evidences negatively impacting female LFPR.

Between 2017 and 2021, there was a slowdown in overall regular wage job creation but formal jobs (with a written contract and benefits) as a share of all regular wage work rose from 25% to 35%. In 2020-21(pandemic year) regular wage employment fell by 2.2 million. But this net change hides an increase in formal employment by 3 million and a loss of about 5.2 million of semi and informal regular wage employment. While half of the lost employment is accounted for by women, only a third of the increase in formal employment accrued to women. So, in net terms, women lost out on formal employment in this period. Not only that, there was a shift towards self-employment due to distress. (IPA Service)

US Supporting Canadian Position On Nijjar Killing Poses A Big Threat To India

US Supporting Canadian Position On Nijjar Killing Poses A Big Threat To India