By Dr. Gyan Pathak

Unless paid and formal employment is guaranteed, a woman’s economic activity in India is associated with a higher risk of intimate partner violence(IPV).However, household and other characteristics, such as higher agency within the household, higher education of the husband, lower social acceptance of IPV, and normalization of reporting incidences of violence counter this association. At the state level, the presence of more female leaders, better reporting infrastructure for victims of IPV, and higher charge-sheeting rates are associated with a lower risk of IPV.

This is the conclusion of a recent IMF working paper titled “Intimate Partner Violence and Women’s Economic Empowerment: Evidence from Indian States”. This paper focuses on, arguably, the most complex barrier – IPV – holding back many women in India and other countries—intimate partner violence (IPV).The findings are crucial, since the country’s female population represents more than one sixth of the global female population. The paper studied the interplay of determinants of a woman’s risk of facing IPV in India using information from upto235 thousand female survey respondents and exploiting state-level variation in institutions, law enforcement and attitudes.

Though several initiatives have been launched focusing on women’s leadership and empowerment, and a range of laws and initiatives aim to protect women and girls from violence, wide gender gaps remain, and the incidence of violence against women remains high, with significant costs to individuals, families, and the economy.

The results of the paper highlighted three key points: First, at the individual level, for most types of employment, a woman being employed and earning more than their partner translates into a higher risk of intimate partner violence. However, when combined with specific interventions, women’s formal and paid employment can reduce the individual’s risk of intimate partner violence. In particular, empowerment and agency at the household level, higher education of men, lower acceptance of intimate partner violence in the state the woman is residing, and normalization of reporting of violence can turn the relationship between female formal and paid employment and intimate partner violence to one in which employment and lower risk of intimate partner violence go hand in hand.

Second, a higher share of women in leadership positions at the state-level is associated with a lower risk of violence for the individual living in that state. Existing studies show that the presence of more female leaders change perceptions of women as workers and contributors to the household’s income.

Third, strong institutions, and especially the enforcement of laws, matter. Better reporting infrastructure for victims of intimate partner violence and higher charge-sheeting rates at the state-level translate into a lower risk of violence for the individual.

The key takeaway is that the complexity of the problem requires a multipronged approach to reduce and eliminate domestic violence, including by empowering women more broadly. Such efforts would foster better living conditions for women and girls, while helping India reap its massive economic development potential.

IPV in India remains high, while women’s participation in paid economic activity is low compared to other countries in the Asia and Pacific region. According to the most recent National Family Health Survey (2019-21), approximately 1 in 3 women in India experienced physical, sexual, or emotional IPV. This rate is higher than in many other countries in the Asian and Pacific region and worldwide. At the same time, India’s rate of female labour force participation is lower than in most counties. With both high levels of violence, and low female labour force participation, India is losing out on significant development and inclusive growth opportunities, says IMF working paper.

The paper points out that the incidence of domestic violence is high and declining at a slow rate in India, and there are large variations across states. The lifetime IPV incidence in India was 31.8 percent in2019-21, down only by 1.5 percentage points compared to 2015. The incidence of physical violence declined from 29.8 percent in 2015-16 to 28.2 in 2019-21, the incidence of sexual violence decreased from 7 percent in2015-16 to 6.1 percent in 2019-21. On the other hand, the incidence of emotional violence increased (+0.2 ppt) to 14 percent in 2019-21. While these rates are high, these averages also mask significant variation of rates across states: For instance, rates are lowest in Goa, Himachal Pradesh, and Nagaland—where the incidence is around 10 percent—and highest in Karnataka, Bihar, and Manipur (up to 50 percent).

The share of respondents who justify wife beating is substantial, with higher acceptance rates among women, while reporting rates of domestic violence are low. The acceptance by women in the latest survey, at 41 percent, is high by any standards. While the female share has decreased, the share of men who justified wife-beating rose (+2 ppts) between2015 and 2019. There is significant variation of acceptance rates across states, which are positively correlated with higher incidences of IPV in these states: In Andhra Pradesh, for instance, as many as 80 percent of women surveyed by NFHS in 2019-21 justified wife-beating for at least one reason, while in Tamil Nadu and Telangana, the figure was around 75 percent. In Uttar Pradesh it was around 36percent. In Himachal Pradesh and Delhi, this share was below 15 percent.

The high incidence of IPV contrasts sharply with the low percentage of women who reported such violence or sought help from any source—official or unofficial. Reporting of IPV to anyone is generally low, declining between 2005 and 2019. Only a small share of women who experienced IPV sought help from unofficial sources (for instance, friends, family, neighbours). Even fewer women who were victims of IPV sought help from official sources (police, doctors, lawyers, social services)—only one in 100did—though rates vary somewhat across states. In Manipur, for example, where the incidence of IPV is 40 percent, only 3 percent of victims sought help from any source, whether official or unofficial. In contrast, in states like Punjab and Goa, where IPV rates are lower at around 10-13 percent, more than 30percent of victims sought help. (IPA Service)

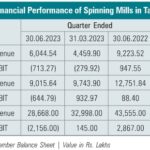

Indian Exports To Bangladesh Facing Problems Due To Payments Delay

Indian Exports To Bangladesh Facing Problems Due To Payments Delay