By Krishna Jha

Growing Unemployment rate is not only a challenge to the economic fabric of the country, it occupies the basic tenet on which a county is assessed. Our country is one of the most populous nations and hence its needs are also different, in both size and resources. The human labour imperative for production and growth has to be supportive of employment generation also. But that is not happening because we are now living in an era of growth without jobs. That precisely means losing the way in a blind alley.

Our country having a past when there was huge migration from rural to urban areas to get non-farm jobs leaving agrarian employment possibilities (70 per cent to 42 per cent) over the last few decades, the past few years have seen a sudden increase in farm-based employment (from 42 per cent to 46 per cent roughly), signalling the return of more than 20 million people (willing to find employment) to farming. There has been a large increase in the proportion of casual, self-employed workers, those employed within the unorganised, informal landscape. These aren’t ‘good’ secured jobs we are talking about, but rather a survival-employment strategy that workers are taking since they are not finding enough opportunities in the secured, organised sector.

The government cited an increase in self-casual-farm sector employment combined as ‘job creation’ happening over the last few years. Even the recent RBI report was craftily designed to validate this ‘fact’ even though key indicators around labour productivity, labour force participation rate (LFPR), sectoral organised employment, real wages, upward mobility in incomes/wealth creation show how such a concocted ‘pattern of employment increase’ is anchored by people’s ability to find work to at least survive, not thrive. Behind this is an exclusive pattern of growth where the labour-substitutive mode of production driven in favour of capital-intensive growth has made ‘good jobs creation’ in the organised sector more difficult, creating uncertainties for the workforce entering the employment scene.

PM Modi’s claim of employment generation referring the RBI data which showed 46.6 per cent increase from 596.7 million to 643.3 million. Had it been true, the expenditure on social security and welfare schemes for workers must have registered a significant increase rather than a sharp reduction from the allocated budgetary provision.

The neglect of workforce by Modi government is most pronounced under the Pradhan Mantri Shram Yogi Mandhan Yojna. Despite the praises like “dignity of labour”, under this scheme the budget has provided Rs 350 crore, which was reduced to Rs 205.21 crore in the revised estimate, however, actual expenditure by the end of 2023 was only Rs 46.34 crore.

Under the Labour Welfare Scheme the budget allocation was Rs 75 crore, which was shown increased to Rs 102 crore, but actual expenditure was only Rs 20.25 crore, the annual report of the ministry shows.

The Centre spent nothing under National Pension Scheme for Traders and Self-Employed Persons under erstwhile Pradhan Mantri Karma Yogi Maan-Dhan Yojna, though it had provided Rs 3 crore in the budget and the revised estimate reduced it to Rs 0.10 crore. Even under Employees’ Pension Scheme it spent only Rs 6875.25 crore as against budget allocation of Rs 9167 crore and revised estimate of Rs 9760 crore.

Even under Aatmanirbhar Bharat Rojgar Yojna, the total allocation was Rs2272.82 crore, which was reduced to Rs1350 crore in revised estimate but total expenditure by the end of 2023 was Rs 1265 crore.

The National Data Base for Unorganised Workers seemed also suffered because the expenditure was only Rs18.63 crore as against budget allocation of Rs 300 crore, and the revised estimate of Rs 102.96 crore.

Modi government had launched the National Career Services with great fanfare but there seems to be little progress in this regard if actual expenditure of only Rs26.36 crore is of any indication against the allocated and revised fund of Rs 52 crore.

Similar is the case with the expenditure of autonomous bodies under the ministry which spent only Rs 94.39 crore as against the budget provision of Rs 127 crore.

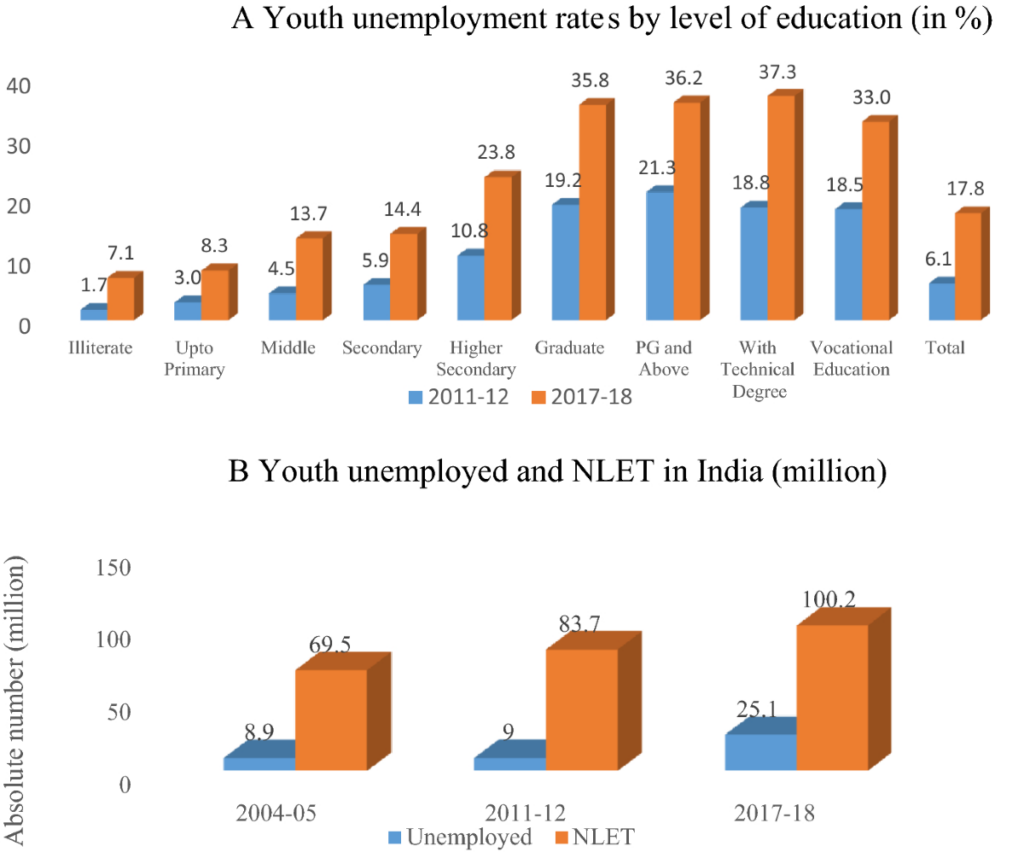

The economy has failed to generate enough jobs for its large and expanding young population. According to the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy, an economic think tank, the unemployment rate was 7.6 percent in March.

Clearly, the Modi government has failed in developing any coherent policy on Manufacturing, agriculture and service sectors. The government expenditure on the development of manufacturing hubs with integrated infrastructure, utilities, and services is pathetic, while the small- and medium-sized manufacturing enterprises that are key to the employment generation are left to fend for themselves. The investment in the health care and education has come down drastically, while the labour laws have been so changed that they provide no security to the workers.

The entire decade has been a decade of near jobless growth. Unemployment issue has brought down the LFPR (labour force participation rate) well below levels. BJP has been indifferent towards taking any initiative to expand the rate of employment in the sectors of infrastructure, manufacturing, and government jobs, the main sources of employment generation.

The growing scarcity of job availability may lead to the risk of missing out on potential demographic dividends. (IPA Service)

Mamata’s ‘I’ll Topple Modi’ Is Open Dare To Prime Minister And NDA Govt

Mamata’s ‘I’ll Topple Modi’ Is Open Dare To Prime Minister And NDA Govt