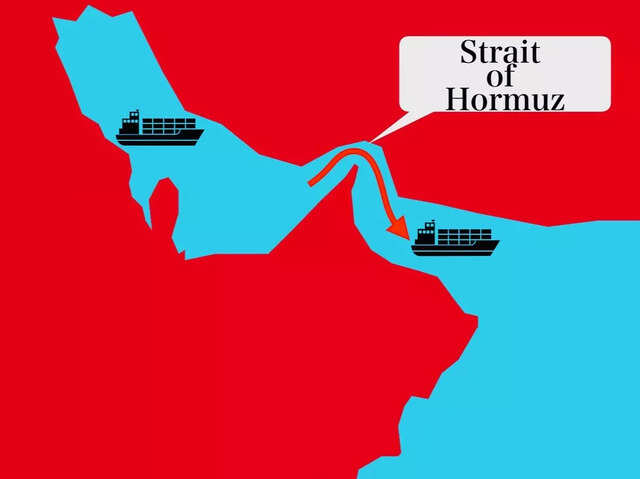

Iran’s parliament has approved a motion to close the Strait of Hormuz, pending final approval by the Supreme National Security Council, following US bombing of key nuclear facilities at Fordow, Natanz and Isfahan. The strategic channel handles about 20 percent of global oil and gas supplies; its closure would disrupt roughly two million barrels per day from India’s imports of 5.5 million bpd.

A Revolutionary Guards commander, Esmail Kosari, told Iranian state media that closure “will be done whenever necessary”, making clear that parliament’s approval is not final and that Iran’s top security body must endorse such a move. Foreign Minister Abbas Araghchi declined to rule out disruption, saying Tehran has “variety of options” to respond.

The backdrop is the US‑Israel air campaign on Iran’s nuclear infrastructure – President Trump announced that three facilities had been “obliterated” using bunker-buster bombs, while Israeli strikes targeted missile sites. In retaliation, Iran launched ballistic missiles at Israel. Gulf states have since heightened alert levels, with Bahrain, Saudi Arabia and Kuwait on emergency footing.

Analysts emphasise the strategic significance of any attempt to close Hormuz. Around 20–25 percent of global oil supply—some 17–19 million barrels per day—passes through the narrow strait, which spans 21 miles at its narrowest, with just two‑mile navigation lanes. While Iran has the means to disrupt shipping—via mining, missile strikes or naval interdiction—experts warn that such actions would provoke a swift and forceful response by the US Fifth Fleet and allied naval forces.

Oil markets are already jittery. Benchmark Brent crude has climbed more than 10 percent over the past week. Traders are monitoring developments closely: a closure, even symbolic, could drive prices past US $100 per barrel, with short‑term spikes of 50 percent not ruled out—though several economists caution any disruption would likely be brief.

Energy‑importing nations, especially in Asia, are facing immediate vulnerability. India, Japan, China and South Korea account for most of the two million bpd affected. For India, which imports 85 percent of its crude and receives nearly 40 percent from the Gulf, any prolonged disruption could worsen inflation and the current‑account deficit.

Despite the threat, analysts at Eurasia Group and BCA Research view parliament’s move as largely symbolic, lacking clear execution mechanisms. History shows Iran has threatened closure but never followed through, recognising the high economic and diplomatic risks. U.S. officials, including Secretary of State Marco Rubio, have warned that any attempt would be “economic suicide” and could prompt military confrontation.

Diplomatic pressure is intensifying. Washington has urged China to dissuade Tehran from taking action, reflecting global concern over economic fallout. Gulf neighbours are on heightened military readiness, fearing escalation beyond Iran’s nuclear sites and into disruption of oil routes.