By Tirthankar Mitra

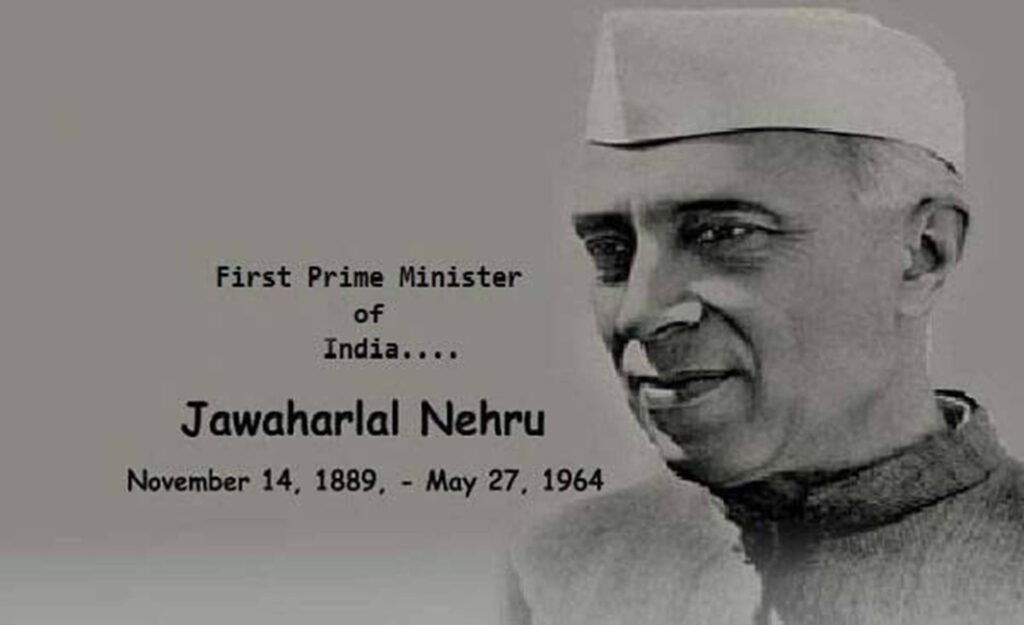

Uniqueness of Jawaharlal Nehru whose birth anniversary is being observed in an arguably muted manner on November 14 lay in his ability to enact the modernity narrative. He was neither chary nor ashamed to accept ideas even it was of others that would take India to new highs on the wings of science and technology following the guidelines of centralised planning.

It is in this respect that Nehru surged ahead of his great contemporaries. They may have been second to none in the love of their country or any lesser in terms of their sacrifices.

Some chose to part ways. Like J B Kripalani and Jaya Prakash Narayan who rose to heights they could not have arguably scaled had they chosen not to break ranks with Nehru and seek political destinies which vastly differed from the one that beckoned them when the nation kept its tryst with destiny.

Many chose to stay in Congress and play second fiddle to Nehru. But once his political fortune dipped and dimmed after 1962 Chinese incursion, these men displayed defiance adding insult to the “Chinese injury” of the man who had propagated Panchsheel.

What these great and small men lacked was the alchemical chutzpah required for the role of a nation builder. It is the possession of this quality which made India’s first prime minister a visionary.

And at the same time he displayed an uncharacteristic political short sightedness at times.. Indeed Nehru did not quite dig in his heels during his negotiations with the last Viceroy, Louis Mountbatten seeking a better deal for a truncated India.

No faithful proponent of intra-party democracy, Nehru displayed some autocratic traits laying the foundation of one man/ one woman rule in Congress. With none other than redoubtable party stalwart Atulya Ghosh recalling in his memoirs Kashta Kalpita this undemocratic trait of his late leader, one need not take it with a pinch of salt.

Even though he remained a great practitioner of parliamentary democracy never failing in his duty as the leader of the House, Nehru was the man who chided his own party MP Lakshmikanta Moitra for his long winded manner of speech. Yet he was the first from the Treasury benchers to congratulate Atal Behari Vajpayee for his oratory and predict that there will be a day when the young Bharatiya Jan Sangh MP will find himself in the Prime Minister’s seat.

Prime Minister Nehru was not beyond cutting short the criticism of government’s policies by a fellow MP at a party conclave. Yet it was the same man who broke into a chuckle going through some of Shankar Pillai’s cartoons on the numero uno Congress leader of the day. Such was Nehru, a man ahead of his times. Yet he is blamed for many of the ills plaguing India nowadays.

Be it foreign policy especially in regard to Sino-Indian relations or for not framing Uniform Civil Code, the name and tenure of India’s first prime minister is being invoked of late for the wrong reasons. It is to heap the blame whenever glitches pile up owing to systemic malfunctioning and threaten to bring the entire machinery to a grinding halt.

Finding faults in Nehruvian programme is an industry these days. But those at work in it are yet to realise that they are eventually acknowledging the wide ranging genius of the man while criticising his signature.

Be it town planning with Corbusier, science with Homi Bhaba, planning with Mahalanobis, design with the Sarabhais: every experiment has his imprint. Nehru was the nation’s biggest institution builder.

Public sector was Nehru’s brainchild. Coexisting with private sector, it provided much needed sustenance when India was a fledgling economy. In this era of job cuts and a prescription for a 70-hour week, it may be proudly recalled to have churned out jobs in humanitarian terms.

It is time to find out what made Nehru stand out in the company of his successors. He reacted with anguish or indignation to incidents which present day heads of state would not even keep at the back of their minds.

Be it the snows in Kashmir or rains in Bombay, writing to a school girl in Cairo or reading the works of a young Indian poet, nothing was too small for the first Indian prime minister. For he was only too aware that if he did not watch the trembling of a leaf, the heart-beat of a nation would be inaudible to him.

For all his days in Harrow and Cambridge, in his heart of hearts Nehru remained an Indian, full of concern and politeness. A prime minister is pressed for time. Nehru was no exception. But he had the time to play with his grandchildren in the morning, chose a rose for his buttonhole and ask why a tribe in central India was being denied their hooch.

A human who was humane, Nehru’s greatness lay in dreaming big. His mistakes were big but open to critique, a trait which his successors and critics do not share with him. (IPA Service)

Akhilesh Faces Big Challenge To His Leadership From Party Leaders

Akhilesh Faces Big Challenge To His Leadership From Party Leaders