By Shanil Yakoob

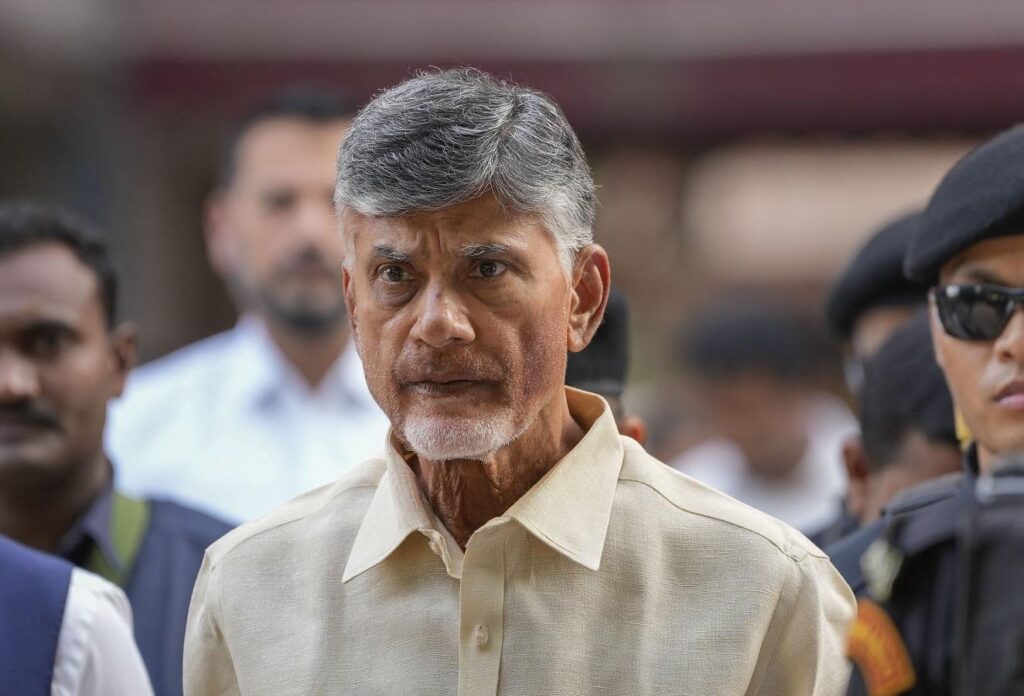

Almost a month to this day, on January 16, 2025, Andhra Pradesh Chief Minister N. Chandrababu Naidu made a startling proposal. Individuals with fewer than two children, he suggested, should be disqualified from contesting local body elections. This announcement came just two months after his government passed the Andhra Pradesh Panchayat Raj (Amendment) Bill, 2024, and the Andhra Pradesh Municipal Laws (Amendment) Bill, 2024. These laws repealed the contrasting condition which previously mandated that anyone with more than two children would be disqualified from contesting elections.

This abrupt shift from a maximum to a minimum child requirement marks an unprecedented departure from established population policies in India. Traditionally, several states have enforced a two-child cap to discourage large families among political representatives in local elections. However, Naidu’s proposal to set a minimum child threshold for electoral eligibility marks a potentially regressive and constitutionally dubious move. It not only defies practicability but also poses serious risks to democratic participation, personal liberty, and gender equity.

Globally, anxieties around falling fertility rates and decline of specific demographic representations have seeped into public discourse across Asia, Europe, and North America. Naidu’s proposal is an indicator that this anxiety has now reached Andhra Pradesh.

In Javed v. State of Haryana (2003), the Supreme Court upheld Haryana’s two-child maximum policy, emphasizing that the right to contest elections was not a fundamental right, but a statutory one. The Court’s rationale was rooted in promoting population control and the trickle down benefits on maternal support and child care in the state. It relied on the National Population Policy (2000), which noted that the policy served “to enthuse communities to be attentive towards the quality and coverage of maternal and child health services, including referral care.”

Andhra Pradesh’s proposed two-child minimum norm, however, turns this logic on its head. In Suchita Srivastava v. Chandigarh Administration (2009) the Supreme Court held that reproductive choices are integral to personal liberty. Mandating childbirth as a precondition for political participation infringes upon this fundamental right. Naidu’s proposal, thus, raises critical questions under Article 21.

The proposal is also unlikely to pass the “reasonable classification” test under Article 14. Derived from the Supreme Court’s decisions in Anwar Ali Sarkar (1952) and E.P. Royappa (1974), the test requires that any classification made by a law must, firstly, have an intelligible differentia, and secondly, bear a rational nexus with the law’s end goal.

The policy of limiting the number of children is ostensibly aimed at population control. But a policy to restrict those candidates who have less than two children lacks rational connection to desired objectives for such laws, such as keeping in check the competence of elected leaders. It discriminates against young individuals, childless couples, LGBTQ+ persons, and those unable to conceive – effectively creating barriers to democratic participation.

Increasingly, enabling political participation has shifted into the realm of a constitutional imperative. In PUCL v. Union of India (2003), a three-judge bench of the Supreme Court recognized the right to vote as an extension of free speech under Article 19(1)(a), while a five-judge Constitution Bench in Kuldip Nayar v. Union of India (2006) reaffirmed that free and fair elections were part of the Constitution’s basic structure. Thus Naidu’s proposal affronts not only free speech, but potentially the basic structure, fundamentally threatening India’s democratic fabric.

Presently, under Articles 243F and 243V of the Constitution, a 21-year-old can lead panchayats or municipalities. Factoring in India’s marital age requirements (21 for men and 18 for women), Andhra Pradesh’s proposed two-child minimum policy would effectively spike up the minimum age for political participation to 24-25 years. This amounts to an implicit amendment of constitutional age requirements without following appropriate legislative procedures – enabling something directly which cannot be done indirectly. This sets a potentially concerning precedent in lawmaking.

The timing of this proposal is jarring for a particular reason. On September 28, 2023 the 106th amendment to the Constitution was passed, which guaranteed 33% reservation for women in legislatures – a long-overdue step towards gender-inclusive governance. Andhra Pradesh’s two-child minimum proposal risks derailing this progress by reducing women’s political legitimacy to their reproductive capacity. The message is clear yet contradictory: “Women are welcome in politics, but only after fulfilling their ‘reproductive duties’.”

In The Second Sex (1953), French philosopher Simone de Beauvoir argues that women have historically been socially essentialised to their reproductive functionality, reduced to “instruments” instead of being acknowledged as “autonomous beings”. Feminist legal theorists like Catharine MacKinnon and Martha Nussbaum have also argue that reproductive control often becomes a tool of subjugation. Naidu’s proposal, by threatening to transform parenthood into a political qualification, potentially denigrates the autonomy of women in Andhra Pradesh.

Naidu’s pronatalist prescription is not unique. Globally, declining fertility rates have prompted anxiety among policymakers, leading to interventions ranging from incentives to coercion. Mary Corcoran, an Irish sociologist and academician argued that nearly 30 percent of countries worldwide have adopted pronatalist policies, a notable rise from just 10 percent in the 1970s. After decades of enforcing the one-child policy, China is now urging its citizens to have more children as it faces a population decline. Officials have been encouraging women to get pregnant, appealing to their sense of duty with messages like “Do it for your country.” Japan, which is facing a 1.2 fertility rate, is set to enact a four-day workweek for state employees from April 2025 to enable better work-life balance. Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan declared 2025 the “Year of the Family,” unveiling financial incentives to encourage childbirth.

India’s fertility rate is declining. In Andhra Pradesh, it is well below replacement levels. However coercive policies to boost population, such as that of Naidu, are not an effective way to respond to this problem. Research suggests that societies with robust support systems – affordable childcare, parental leave, flexible work policies, and gender equality – sustain healthier fertility rates.

Contrast this with intensive work culture in India’s corporate spaces. Recent remarks by industry leaders like L&T’s S.N. Subrahmanyan, who proposed a 90-hour work week and Infosys founder Narayana Murthy’s 70-hour work week proposal are emblematic of an increasing cultural idealisation of imbalanced work-life dynamics. It is also a serious impediment to emotional well-being, and ultimately to sustaining family lives.

Thus India’s appropriate response to demographic decline concerns is to recalibrate its policies in a way such that emerging population concerns are addressed without trampling upon fundamental rights of the citizens, or democratic principles. Prioritising the strengthening of maternity and paternity support working parents, ensuring access to affordable childcare, and introducing flexible work policies that enable a better work-life balance are more promising, alternative options. Additionally, sustained investments in quality education and healthcare could empower families to make informed reproductive choices while fostering a supportive environment for raising children, thereby aligning demographic goals with the principles of personal freedom and social equity.

The underlying question in such policies has little to do with demography, and more specifically about whether we prioritise inclusivity or conditionalise democratic participation. Women, young people, people on the spectrum, and childless individuals cannot, by any principled measure, be excluded from exercising their rights as citizens simply owing to their reproductive status. Leadership in elected democracies stems from capability, vision, and service – not from the number of children one bears.

Naidu’s proposal awaits legislative scrutiny, but its implications resonate far beyond Andhra Pradesh. Coercive population policies, whether restricting or mandating childbirth, have no place in a rights-based democracy. (IPA Service)

Courtesy: The Leaflet

Trump’s Unilateral Tariff Hike Is A Challenge To International Trade Order

Trump’s Unilateral Tariff Hike Is A Challenge To International Trade Order