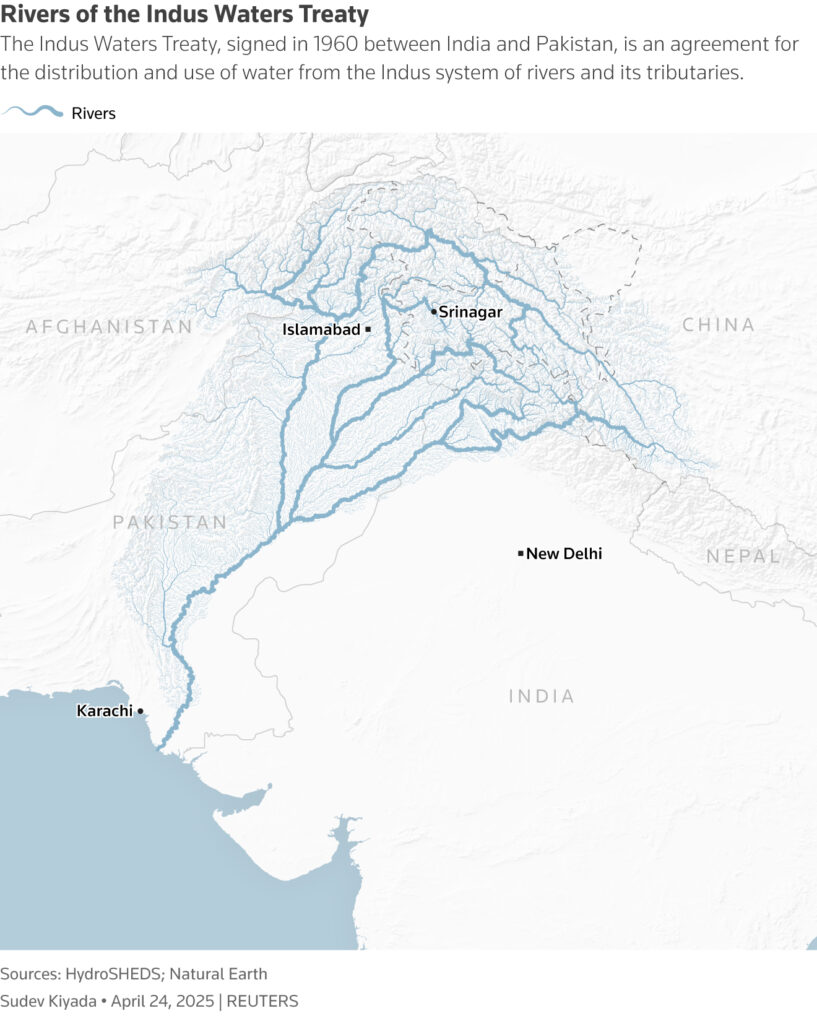

Tensions surrounding the Indus Waters Treaty are mounting, with the Indus, Jhelum, and Chenab rivers poised to become new focal points in the long-standing dispute between India and Pakistan. The treaty, signed in 1960 by then Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and Pakistan’s President Ayub Khan, has faced persistent criticism from segments within India, notably the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh , which has long regarded the agreement as disadvantageous to Indian interests. Recent actions suggest India is moving toward significantly altering its stance on the pact, raising concerns about the future management of these vital waterways.

The Indus Waters Treaty was designed to allocate the waters of the six rivers of the Indus basin, granting control over the eastern rivers—Ravi, Beas, and Sutlej—to India, while the western rivers—Indus, Jhelum, and Chenab—were largely allocated to Pakistan. The treaty established a framework for cooperation and conflict resolution over water sharing, surviving multiple wars and enduring geopolitical tensions between the two nations.

Calls for abrogation of the treaty have gained traction within Indian political and ideological circles, particularly from the RSS, which views the treaty as an outdated relic that disproportionately limits India’s utilisation of water resources in Jammu and Kashmir and Himachal Pradesh. The organisation has argued for years that India’s upstream rights have been curtailed, hampering development projects critical for energy production and agriculture.

Former Indian Prime Ministers Atal Bihari Vajpayee and Narendra Modi both reportedly entertained the possibility of revising or scrapping the treaty after significant security incidents involving Pakistan-based militant groups, including the Kargil conflict in 1999 and the Uri and Pulwama attacks in 2016 and 2019 respectively. These events intensified calls within India to reassert control over the western rivers, perceived as potential leverage against Pakistan.

Following the Pulwama attack and the subsequent air strikes at Balakot, India’s approach to the treaty became more assertive. The decision to review and modify the water-sharing arrangements marked a shift from decades of adherence to the treaty’s provisions, signalling a readiness to prioritise strategic and developmental needs over longstanding diplomatic agreements.

India’s unilateral steps have included the approval of multiple hydroelectric projects on the Chenab and its tributaries, which Pakistan has challenged, arguing that these violate the treaty’s restrictions. India maintains these projects conform to treaty provisions that allow limited use of the western rivers for hydropower and irrigation. However, Pakistan views such projects as attempts to restrict downstream flow, threatening its own agricultural economy and water security.

The Indus Waters Treaty has historically been regarded as one of the most durable agreements in the world, enduring despite the absence of diplomatic relations and military confrontations between the two countries. The treaty’s Permanent Indus Commission, comprising commissioners from both sides, has served as a mechanism to resolve disputes and facilitate dialogue. Yet, its effectiveness has been increasingly questioned as political tensions escalate.

The strategic significance of the Indus basin cannot be overstated. For Pakistan, the Indus river system provides around 90% of its water supply, crucial for its agriculture-based economy. Any disruption or perceived unfair utilisation by India risks exacerbating water scarcity issues, particularly in Pakistan’s Punjab and Sindh provinces. For India, the upper riparian position offers opportunities for hydropower development and enhanced water management in the northern states, especially in Kashmir.

Analysts note that water resources in the region are becoming more contentious as climate change alters river flows and intensifies water scarcity. With populations growing and demands rising on both sides, the treaty’s frameworks, drawn up over six decades ago, may no longer reflect the contemporary hydrological and political realities. This has led some experts to call for a comprehensive review and renegotiation, although the prospect of outright abrogation raises concerns about triggering a wider conflict.

Diplomatic efforts to manage the dispute continue, but mistrust and nationalist sentiments hinder constructive dialogue. Pakistan has warned that any attempts by India to unilaterally change the status quo could escalate tensions and impact broader bilateral relations, including security and trade. India, on the other hand, asserts that its actions are within legal rights and necessary to harness its resources for development.

Water experts also point to the environmental consequences of disrupting the established water-sharing regime. Alterations in river flows could damage ecosystems downstream, affecting fisheries, wetlands, and biodiversity. There is a call for both countries to consider sustainable water management practices that balance development with ecological preservation.

The international community remains attentive to developments regarding the Indus Waters Treaty. Given the strategic importance of South Asia and the history of conflict between India and Pakistan, any escalation in water disputes carries implications beyond bilateral relations, potentially affecting regional stability and cooperation on transboundary resources.

As India continues to advance hydroelectric projects on the western rivers, Pakistan’s objections have led to legal battles, including referrals to international arbitration under treaty mechanisms. The outcomes of these disputes may shape the future operational framework of the treaty and set precedents for water diplomacy in contested regions.

Congress G-23 Emerges as Party’s Key Defenders Amidst INDIA Bloc Rift

Congress G-23 Emerges as Party’s Key Defenders Amidst INDIA Bloc Rift