By Tirthankar Mitra

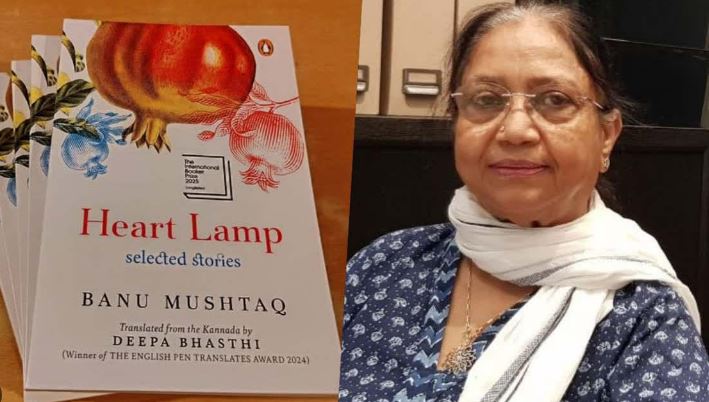

Heart Lamp written by Banu Mushtaq and translated into English by Deepa Bhasthi has won the International Booker Prize for translated fiction. This heartening news is a tribute to the richness and diversity of the regional Indian literature..

This collection of short stories is a journey of words. It needs to be mentioned that without dexterous translation serving as the proverbial bridge between languages and cultures, it would have remained just another good book written in Kannada.

Incidentally, Mushtaq is the first author in Kannada to win this prestigious award. There are many firsts about this book. Bhasthi is the first Indian translator to taste Booker success. Mushtaq’s book comes three years later after Tomb of Steel penned by Geetanjali Shree and Daisy Rockwell won the Booker award.

This is the second time when a Kannada author has been recognised by Booker institutions. U R Ananthamurthy was nominated in 2013 for the body of his works. Heart Lamp is a triumph of India’s diversity, literary, linguistic and otherwise. It hails the country’s pluralistic face.

Mushtaq drew on personal experiences as well as reported incidents. He draws closer to her readers when she said “My heart itself is in my field of study”. Bhasthi, the first Indian translator to win this prize earlier won English PEN’s award for translation. “For me, translation is an instinctive practice” she said.

The book underscores the depth and diversity of Indian languages besides doing Kannada proud. It is another indicator of the global interest in Indian literary endeavours. Mushtaq’s portrayal of the lives of women from the minority community is topical. More so as efforts are on to tar this community.

There is a quiet power about Heart Lamp. And it ought to be no surprise as Mushtaq wears the hats of lawyer, journalist, author and activist. Born in 1948 in Hassan, Karnataka she writes with a rare empathy about the women of her community. There is no effort to look away from surrounding pain in Heart Lamp’s stories.

The protagonists deepen the portrayal of suffering. Their efforts to shake off their burden of gender make them stand out. The women in Heart Lamp neither seek pity nor demand applause. Their state of being inform readers of quiet revolutions lit by a single spark apparently far from the combustible bundle of latent emotions.

In its own way, Heart Lamp ‘s author fights against efforts of marginalization of a community. Long after the adulation around Mushtaq ceases, Heart Lamp’s readers will continue to ask questions.

They will be mostly about reasons behind discrimination on grounds of faith, gender and caste. Therein lies the claim to timelessness of the efforts of Mushtaq and Bhasthi. But glory and the praise in its wake have not severed Mushtaq from reality. Her head and heart are in the right place to which her acceptance speech is a pointer. In it, she had thanked her readers for letting “her words wonder into (their) hearts”. Few expressions of gratitude could have been more genuine and moving. (IPA Service)

Will India Really Shift To Four Day A Week Spanning 48 Hours?

Will India Really Shift To Four Day A Week Spanning 48 Hours?