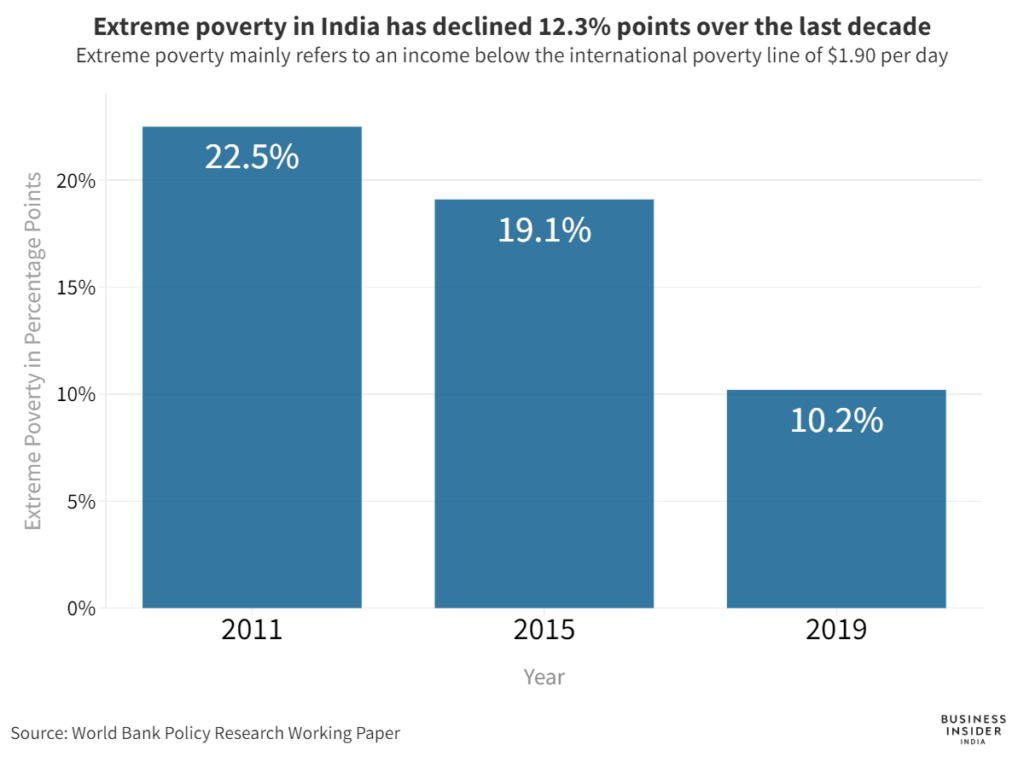

NEW DELHI: India has made significant progress in reducing poverty, with extreme poverty — measured at $2.15 per day in purchasing power parity (PPP) terms — falling from 16 per cent in 2011–12 to 2.3 per cent in 2022–23, according to the World Bank. The decline lifted 171 million people above the internationally comparable poverty line.

In a brief on poverty and equity, the multilateral lender noted that rural extreme poverty in India fell from 18.4 per cent to 2.8 per cent, while urban extreme poverty dropped from 10.7 per cent to 1.1 per cent during the same period. The rural-urban gap narrowed from 7.7 to 1.7 percentage points, translating to an annual decline of 16 per cent in this divide.

Applying the $3.65-per-day poverty line for lower-middle-income countries (LMIC), poverty fell from 61.8 per cent to 28.1 per cent, pulling 378 million people out of poverty. Rural poverty at the LMIC threshold dropped from 69 per cent to 32.5 per cent, while urban poverty declined from 43.5 per cent to 17.2 per cent. The rural-urban gap narrowed from 25 to 15 percentage points, reflecting a 7 per cent annual decline, the World Bank said.

The World Bank’s multidimensional poverty index (MPI), which includes extreme poverty but excludes nutrition and health deprivation, showed that non-monetary poverty declined from 53.8 per cent in 2005–06 to 16.4 per cent in 2019–21, and further to 15.5 per cent in 2022–23.

“Data on consumption is not comparable any more since the methodology has changed. There has to be focus on collecting data from independent sources such as Census, National Family Health Survey. All these issues raise questions (on poverty decline),” said N C Saxena, former secretary of the Planning Commission.

The World Bank said its poverty estimates for India are based on the 2011–12 Consumption Expenditure Survey (CES) and the 2022–23 Household Consumption Expenditure Survey. “Changes in questionnaire design, survey implementation, and sampling in the 2022–23 survey represent improvements but present challenges for making comparisons over time. Moreover, sampling and data limitations suggest that consumption inequality may be underestimated,” it noted.

India’s five most populous states — Uttar Pradesh, Maharashtra, Bihar, West Bengal, and Madhya Pradesh — accounted for 54 per cent of the country’s extreme poor in 2022–23 and 51 per cent of its multidimensionally poor in 2019–21. These states had contributed 65 per cent of the extreme poor in 2011–12 and drove two-thirds of the overall decline by 2022–23.

Poverty estimates will change with revisions to international poverty lines and the adoption of 2021 PPPs, the Bank said. “Under a revised extreme poverty threshold of $3 per day and a lower-middle-income line of $4.20 per day, the 2022–23 poverty rates would be adjusted to 5.3 per cent and 23.9 per cent, respectively,” it added.

The report also flagged persistent wage disparities in India. In 2023–24, the median earnings of the top 10 per cent were 13 times higher than those of the bottom 10 per cent. While India’s consumption-based Gini index improved from 28.8 in 2011–12 to 25.5 in 2022–23, the Bank said inequality may still be underestimated due to data limitations. The World Inequality Database indicated income inequality has risen, with the Gini coefficient climbing from 52 in 2004 to 62 in 2023.

On employment, the World Bank brief said youth unemployment stands at 13.3 per cent, rising to 29 per cent among tertiary-educated graduates. Only 23 per cent of non-farm paid jobs are formal, while most agricultural employment remains informal. Self-employment is on the rise, particularly among rural workers and women. Despite a female employment rate of 31 per cent, gender disparities persist, with 234 million more men in paid employment.

The report noted, however, that since 2021–22, employment growth has outpaced the expansion of the working-age population.

Source: Business Standard

Government Notifies Goods & Services Tax Appellate Tribunal Rules

Government Notifies Goods & Services Tax Appellate Tribunal Rules