By Pradip Baksi*

The émigré communist journals arrived clandestinely into India from the beginning of the 20th century. The first communist journals from within the country also made their appearance. In all these publications, Marx and Engels appeared as the ideological ancestors of Bolshevism. Since then, the communists and their followers were the principal propagators of the teachings of Marx and Engels in India. Some non-communist members of the academic profession also took some initiative.

Historians of the communist movement of India have, so far, identified several anti-British-imperialist trends which went into its formation. These are: the émigré patriotic trend operating from Germany, the USA, Turkey and Afghanistan; the Pan-Islamic Khilafatist Muhajirs operating from Afghanistan; the Sikh and Punjabi émigré labour movement in the USA and Canada organised around the Ghadar Party (some of its members operated from the Latin Americas); while within the country we had the left wings of the Indian National Congress, the various Hindu militant organisations and groups, the Khilafat movement, and the Akali movement of the Sikhs, chiefly. The members of these trends carried with them their already acquired casteist, parochial, communal, religious, xenophobic, national, patriotic, anarchist and socialist understanding of India and the world. Often their ideology was a hybrid of one or more of these worldviews, mingled with their newly acquired Bolshevik understanding of Marx.

These hybrid forms of consciousness arose from a social soil, where, following the European colonial interventions, ‘‘a whole series of economic systems’’ grew upon the social formations based on ‘‘decomposed communal property.’’ Our politicians and members of the academic community, interested in Marx and Engels, share these multi-faceted forms of modern Indian consciousness. But there is an important difference among them. According to one view, the academic profession in modern India came into existence in a society which was ‘‘not a civil society, it could not develop a sense of affinity with the other sectors of the elite — alien and Indian — which ruled the Indian polity, economy and culture. And being more advanced in scale on which it was carried on than the economic and social structure of the country, it could not function as an effective training stage for the central and lesser elites of the country . . . The attrition of civility and superfluity in the performance of its function in the Indian economy have inhibited intellectual ardour and hampered the growth of intellectual traditions.’’

According to another view, the Asiatic mode of production did have a civil society, though it appears less articulated when compared with its counterpart under capitalism. Within the overall dominance of the varnic / caste-wise division of labour, a kind of civil society grew in the ancient Indian towns. The Arthashastra (c. 300 B.C.-150 C.E.) of Kautilya and the Kamasutra (c. 300-400 C. E.) of Vatsyayana reflect the existence of rule-governed contractual relations. Later on this civil society was crossed with several Central Asian and peripheral Persian strains. Finally, the European colonial powers — Portugal, France and England — crossbred some Eurasian civil societies in some towns. The present Indian governments are at once extending and limiting their domains. Instead of a civil society giving rise to a corresponding political society, it is a case of a hybrid political society introducing and controlling several hybrid civil societies from above.

In ancient India, academic activity was the sole preserve of a thin layer of Brahmans. Indian Islam kept it limited among the Ashrafs — Saiyads, Sheikhs. In the Mughal, colonial and post-colonial periods, members of a couple of other ‘upper’ castes — the Kayasthas, Vaidyas — entered into the academic profession. It is still predominantly an ‘upper’ caste preserve. They have also effectively appropriated the media, the executive, the courts, the political parties, including the communist parties, and the parliament. Be it noted that not a single Indian author referred to in the present article belongs to any of the ‘lower’ castes and tribes of India. The market is the domain mainly of the Banias. The currently dominant ‘fresh class’ is a cluster of coalitions of the partially westernized sections of these ‘upper’ castes. The contractual relations they enter into are still largely determined by their caste status in the society. Right to property, though a statutory right, is not a fundamental right in India today.

Even in the post-colonial period, the industrial worker is a ‘‘peasant manqué’’, a peasant at heart. Marriages among the majority community of Hindus are still largely caste- endogamous and gotra-exogamous at the same time. This militates against vertical social mobility, right from the level of child rearing practices, governed by caste-specific paradigms. It appears that like the crossbred strains in the plant world and animal kingdom the crossbred civil societies also require continuous backcrossing, for the retention and enhancement of their vitality. In the absence of such backcrossing they falter, stagnate; the linkages among the academic, central and lesser elites get fractured. The history of reception of Marx and Engels in India is unfolding inside this larger history of further articulation of the civil societies in this sub-continent, straddling several socio-historical time-zones — from that of the hunter-gatherers to that of the netizens — here and now.

A founder of the Communist party of Mexico in 1919, Manabendra Nath Roy (original name, Narendra Nath Bhattacharya), wrote, when no longer a communist, that he had accepted socialism in 1916, but not ‘‘its materialist philosophy.’’ Another early Indian admirer of Bolshevism, Maulavi Mohammad Barakatullah wrote in 1919, that ‘‘Karl Marx founded the lofty structure of socialism in the 19th century’’ basing himself on the basic principles propounded by ‘‘Plato, the divine man’’, in his book called the Republic. Barakatullah saw in Bolshevism the fruition of the spirits, not only of Plato, but also of Judaism, Christianity and Islam.

Yet another admirer of Bolshevism, who later on became one of the leaders of the Communist Party of India, approvingly wrote in 1921: ‘‘Bolshevism is not, like other sciences, simply a science of politics and economics, submitting itself to changes due to criticism, a true Marxian or a Bolshevik will admit of no change in the body of the theories of his faith. Karl Marx’s Book the ‘‘Capital’’ is to the Bolshevik what the Geeta [Bhagavad-Gita] is to the Hindu, or the Bible to the Christian. Day by day the very inspirer Karl Marx is passing into a Mythical Being. Bolshevism has come to acquire a force of religion, and all that inspired unflinching belief, that a religion demands.’’

This registration of the religious ‘moment’ in Bolshevism, of the theologization of the Capital and, of the mythologization of Marx, immediately reminds one of Engels’ statement, that ‘‘The history of primitive Christianity presents peculiar points of affinity with the modern labour movement.’’

Speaking of later Christianity and later Marxism, a radical Christian historian of Marxism-in-India observed that: ‘‘Marxism came to India in its generalized catechism form of Marxism-Leninism.’’

And that: ‘‘[T]here is a similar relation between the historical and political economic writings of Marx and Stalin’s doctrinal system, as between the biblical texts and some scholastic system of church doctrine. Both developments are connected with the process of institutionalization and exercising power.’’

One may add, that similar relations are also observed in respect of the Vedas and the later codification of brahmanic Hinduism in the Smrtis and in the subsequent commentaries, as well as in the case of the teachings of Buddha and their subsequent transformation, culminating in the history of Buddhism in Tibet.

Engels’ Der Ursprung der Familie, des Privateigentums und des Staats was the first text that was translated into an Indian language, before any other work of Marx or Engels. An activist of the anti-British freedom movement, and widely travelled economist and sociologist, Professor Benoy Kumar Sarkar prepared a free Bengali rendering of it, while residing at Lugano in Switzerland, and got it published from Calcutta, under a changed title. Sarkar defended the change in title with the argument that private property is not the main issue in Engels’ text; the main issue there is the history of three centres of human life: the family, the gens and the state. However, he observed that questions related to private property are close to Engels’ heart.

Hence, perhaps, the subtitle: (An Economic Interpretation of History). Sarkar did not provide any editorial remark or note on the various India-related references found in this text. Same is true of the later exact Bengali translations of this text. Sarkar noted, that Marx and Engels are being worshiped by the workers and poor people all over the world, as the greatest preceptors of the age; that the second and third volumes of Marx’s Capital, the ‘‘Gita of Marx’s principles’’, everywhere shows the marks of Engels’ free editorial hand. He wrote, that the opinions and words of Marx and Engels are not to be treated as the Hindus treat the Vedas; these are to be tested against facts

In the following year the émigré communist journal Masses reprinted Marx’s NYDT article titled ‘‘The Future Results of British Rule in India.’’ One does not know how many copies of it reached the readers in India. A year later, Rajani Palme Dutt of the Communist Party of Great Britain used some of the India-related writings of Marx and Engels in one of his books on India. Its Bengali translation was serialised in the journal Ganabani, from its 12th issue dated 28 April, 1927.

The first free Bengali rendering of the Manifesto of the Communist Party (1848) was also partly serialised in the same Ganabani, organ of the Bengal Provincial Branch of the Workers’ and Peasants’ Party of India — a legal mass political party that provided cover for the members of the illegal Communist Party of India. Later on, it was published as a monograph, under a changed title. The translator, who was then a communist, did not provide any remark defending the change in title. This edition does not contain Engels’ footnote to the famous first sentence of the first section of this text: ‘‘The history of all hitherto existing society* is the history of class struggles.’’

This footnote was added to the 1888 English and 1890 German editions of the Manifesto. This is the only India-related footnote added to this text. It draws our attention to the pre-class and non-class social relations and conflicts observed in many parts of the world, India included. Lack of awareness about or, glossing over of this aspect of the world-historical concerns of Marx and Engels led to many of the later Marxist, Universalist, mechanical and dogmatic imposition of the class-struggle schemata, on any and every sector of any and every society. (IPA Service)

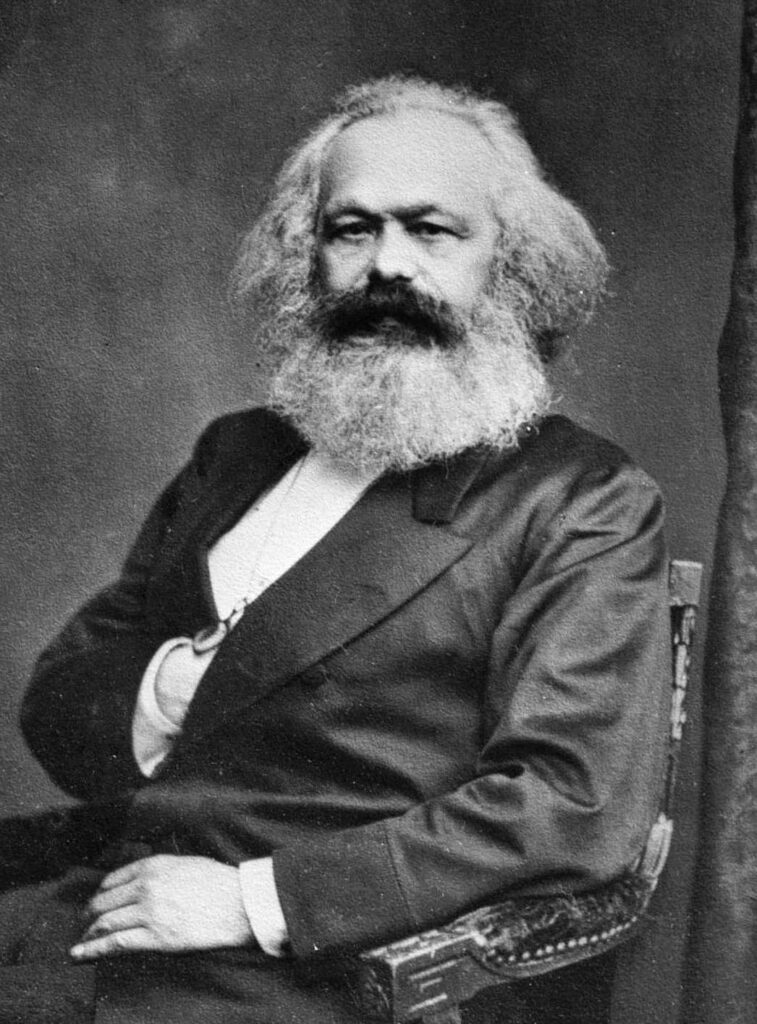

**This is the second of the three part article. The first part was released by IPA on May 5, the 207th birth anniversary of Karl Marx.

* Pradip Baksi is a noted Marx scholar based in Kolkata.

Modi Govt Needs To Cool Off The War Heat, Quell Rumour Mongering

Modi Govt Needs To Cool Off The War Heat, Quell Rumour Mongering