By Maknoon Wani

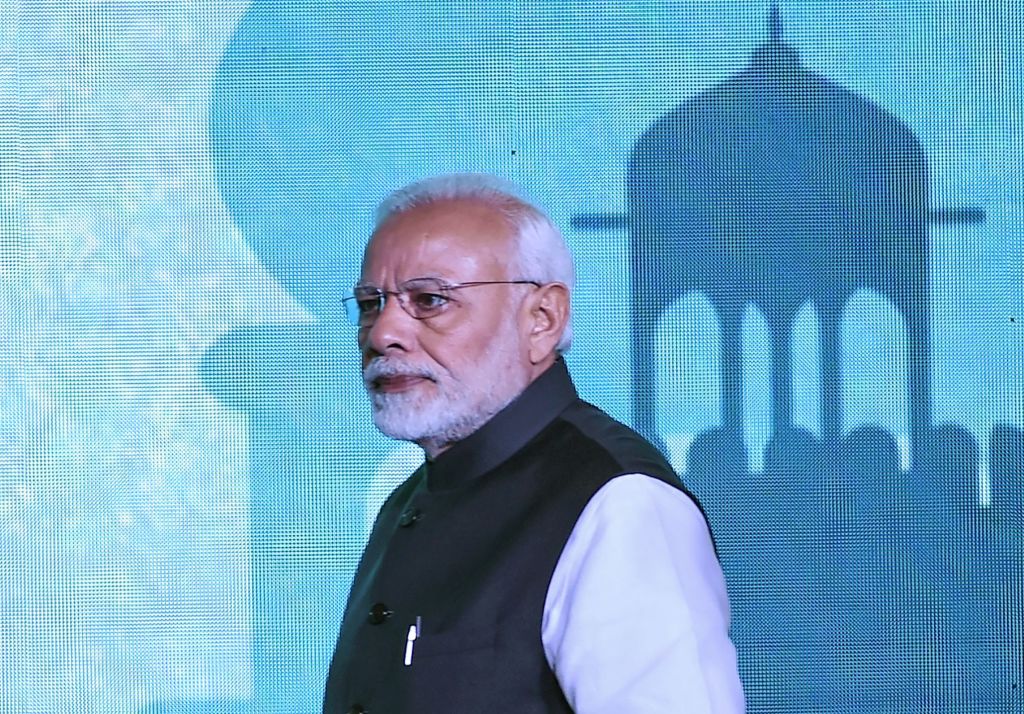

It has been nine years since Narendra Modi’s Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) came to power in India. During that time, Modi and his party have launched an escalating crackdown on their political opponents and media critics.

In March of this year, Rahul Gandhi, one of India’s most prominent opposition leaders, was convicted of defamation for a speech he had made attacking Modi in 2019. Defamation is a criminal offense in India, and Gandhi received a two-year prison sentence as well as being excluded from India’s parliament.

Many journalists have been jailed for reporting on issues that displeased Modi’s government. The Indian authorities have raided the offices of human rights organizations like Amnesty International and frozen their bank accounts, accusing them of money laundering. In February of this year, there were raids on the BBC’s local offices after the British channel broadcast a documentary that criticized Modi’s handling of the 2002 anti-Muslim violence in Gujarat when he was the state’s chief minister.

Most of the Indian media supports Modi and has either misrepresented this crackdown or ignored it altogether. New Delhi Television (NDTV) was one of the last remaining news channels that maintained a semblance of neutrality and reported on uncomfortable issues. However, a wealthy Gujarati businessman and Modi supporter, Gautam Adani, recently purchased NDTV in a hostile takeover. Many of NDTV’s leading news anchors resigned after the takeover, anticipating a change in its editorial policies.

With near-total control of the conventional print and broadcast media, one can only find unbiased and critical reporting in the independent news platforms that are available online. But Modi and the BJP are now seeking to crack down on the space offered by the internet for dissenting voices. The moves it is making could establish a wider template for authoritarian control of online space and platforms.

Over the last year, the Modi government has brought forward a series of laws and regulations that will fundamentally change how the internet operates in the country. The newly amended Information Technology (IT) Rules, first introduced in 2021, allow for the establishment of a “fact-checking unit” to determine the truthfulness of online posts that are related to the government’s activity.

Any post, opinion, or news report that the fact-checking unit deems to be false will have to be removed from social media platforms. In other words, the government will have the power to decide what people are allowed to say about it online.

The principle of safe harbour, which protects online platforms from legal action for content posted by their users, is a cornerstone of the modern-day internet, ensuring that social media providers do not have to overregulate and can maintain a certain level of free speech. However, these protections might now be removed in India. Modi’s junior IT minister, Rajeev Chandrasekhar, recently claimed that the safe harbour principle was responsible for “toxicity” on the internet and could be done away with.

The Modi government has already forced platforms like Twitter to remove user content that criticized its policies. By invoking the spectres of hate speech, misinformation, and fake news, it is seeking to legitimize political censorship of the internet.

The plans for control don’t end there. At an event last November, the Indian foreign minister S. Jaishankar referred to his doctorate on the Manhattan Project in the United States, which led to the development of the atomic bomb.

Jaishankar used this example to stress how important it is to “restrict” and “steer” the use of technology. He went on to speak about the political implications of technology and suggested there was growing concern about where people’s data was being stored and who would collect and process it.

The speech gave us a sense of how the Modi government wants to manage the internet and the tech sector in general. It does not see the internet merely as a tool for economic growth and social change but also as a political battleground that it must dominate and exploit in order to control the country’s citizens. The overriding objective is to create an online ecosystem with multiple levels of government control.

Take the example of the proposed Digital Personal Data Protection Bill that Modi introduced in November 2022. The new law imposes several duties on companies collecting data on Indian citizens, yet it allows the Indian state to exempt its own agencies from most of these provisions, even though it is one of the largest data collectors in the country.

State bodies gather data on the people of India through welfare schemes and biometric identity databases like Aadhaar, a twelve-digit unique identity number that is the largest system of its kind anywhere in the world. In effect, the authorities will be allowed to store data for indefinite periods of time and use it for any purpose they deem fit. These provisions go against the standards established by legislation like the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which enforce limitations on the storage of data and the uses to which it can be put so as to protect the rights of citizens.

The Indian government has been promoting public technologies such as the Unified Payments Interface or UPI, which allows for instant real-time payments through smartphones. This is being done under the rubric of India Stack, a cluster of digital public goods that the government is developing, which will collect even more data from the public. The lack of privacy safeguards means that this data can be used for surveillance and public monitoring without people’s consent.

The government has recently expanded the scope of Aadhaar to the private sector. Having previously been restricted to government agencies, the database will now be available to private companies if they can justify such use as being “in the interest of the state.” The proposed changes do not define what such interests might be.

As the usage of Aadhaar authentication increases, the authorities will inevitably acquire more data. The absence of a data protection law and the exemptions granted in the proposed legislation create a greater risk of arbitrary surveillance.

For example, the state might record the use of a service from any private company through an Aadhaar identity. There are no legal restrictions on how it chooses to deploy that information, and the legislation may even facilitate its use for surveillance. The centralization of financial, biometric, and other forms of data without privacy protections will create a favorable environment for a mass surveillance system.

The BJP administration is also trying to control and monitor private messages. In March of this year, the Financial Times reported that Modi’s government was looking for new surveillance software to replace Pegasus. The military-grade spyware developed by Israel’s NSO Group caused a huge uproar in India last year when the government was accused of deploying it against critical journalists, academics, and politicians.

The Financial Times noted that the “PR problem” associated with Pegasus had prompted the search for a replacement that would be similar but more discreet. The following week, India’s Hindu newspaper reported that an Indian defence agency had already been purchasing equipment from Cognyte, an Israeli firm, to replace Pegasus.

The Indian authorities cannot access private, encrypted messages on apps like WhatsApp and Signal. Existing surveillance laws such as the Information Technology Act prohibit the use of spyware to hack into mobile phones and apps. Several lawyers have informed me that evidence collected using such spyware would not be admissible in an Indian court.

With this in mind, the Modi government introduced the Indian Telecommunications Bill last year, expanding the scope of government surveillance to digital services, including encrypted messaging apps. The bill will allow the government to suspend or surveil communication channels without a court order and without having to make the reasons for doing so public.

The new legislation will force the messaging platforms to break encryption themselves and hand over private messages to the authorities. Messages obtained in this manner will then be admissible as evidence in court. The secrecy and lack of independent oversight makes this bill a dangerous tool that the government will be able to use against its political opponents. It formalizes clandestine surveillance, leaving people with no legal recourse against such monitoring.

Put together, we can identify a three-pronged approach by Modi and the BJP that involves the control of online discourse, the repurposing of public data for surveillance, and the access to private messages. It will transform how the internet is used in India and discourage the expression of dissent, even in private chats, let alone public posts. This legislative blitzkrieg strikes at fundamental principles of the internet, including free speech and the free flow of information.

The new laws will assume greater importance in the run-up to next year’s general election. The BJP will probably seek to use the new legislative levers to dominate online debate. The government’s approach to the internet is rooted in paranoia and a desire to control and monitor information, not just to deal with external threats but also to neutralize domestic opponents and subvert the democratic process. (IPA Service)

Courtesy: Jacobin

Sporadic Violence Continues In Manipur, Despite Amit Shah’s Efforts

Sporadic Violence Continues In Manipur, Despite Amit Shah’s Efforts